Collection Contemporary Art: 1975-Present

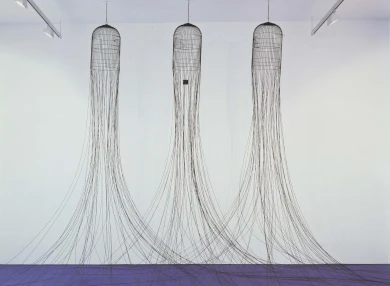

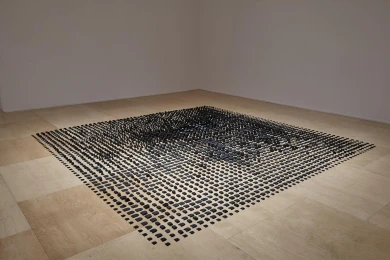

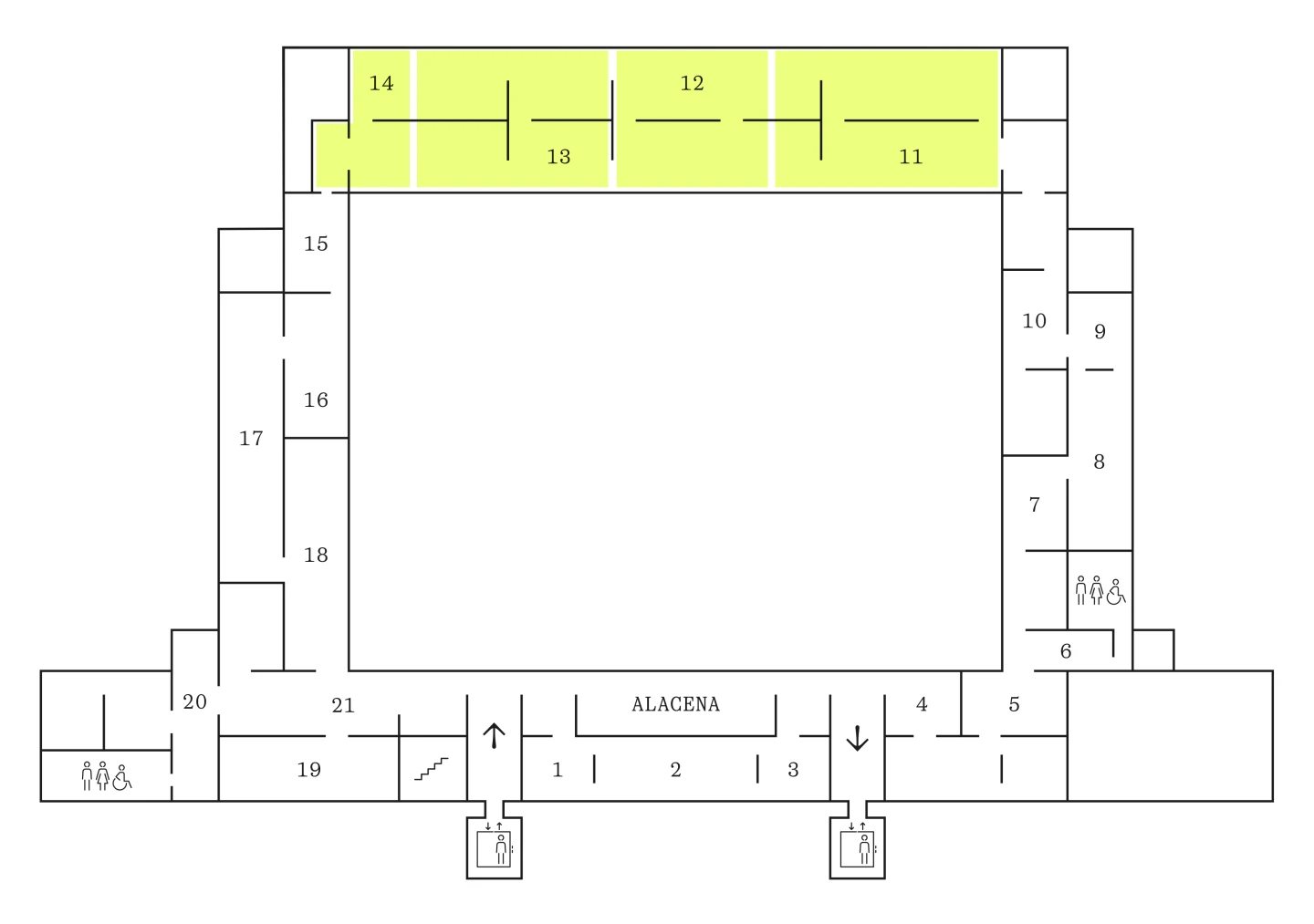

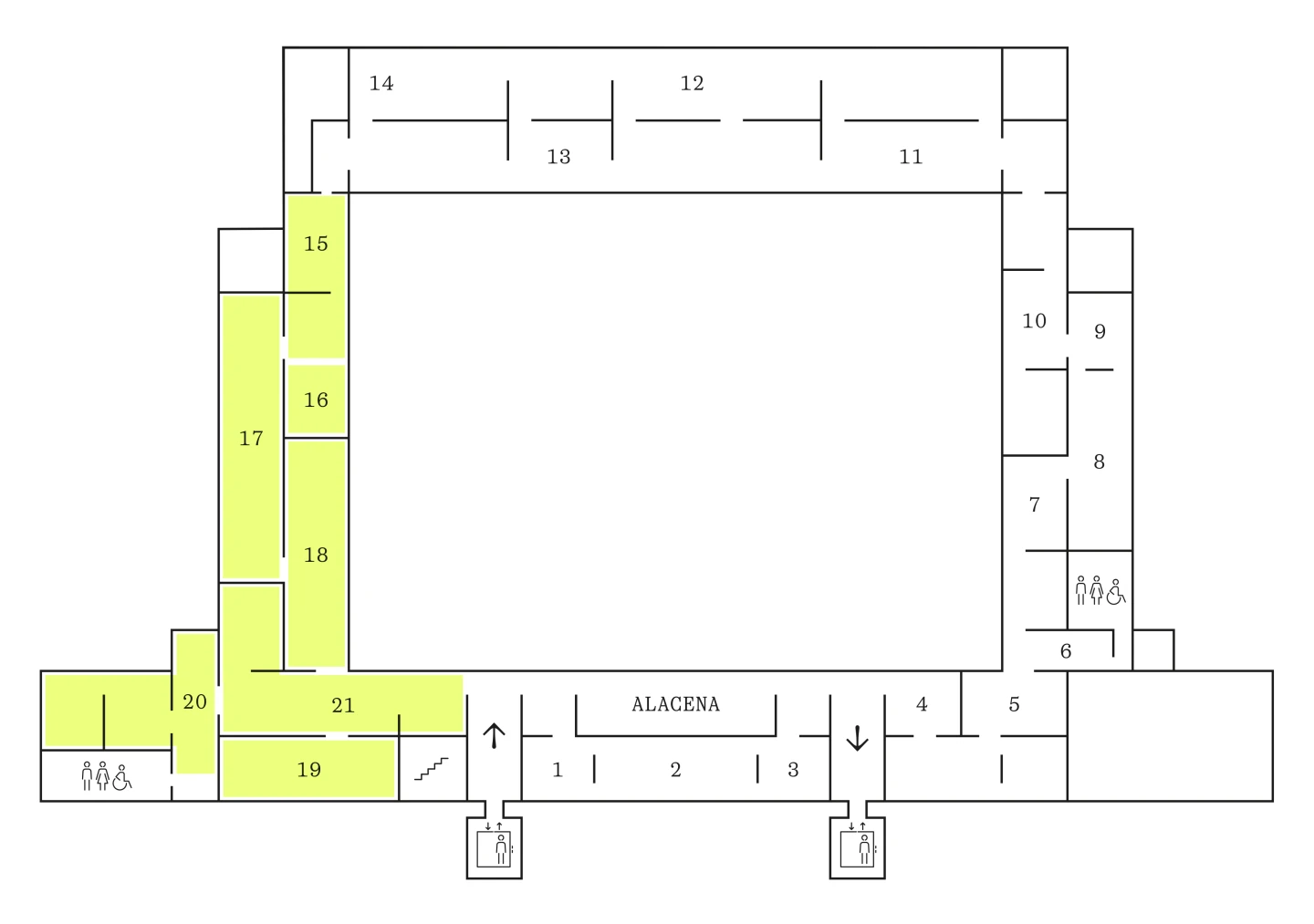

Sabatini Building, Floor 4

This floor tells the history of art of the last fifty years through a selection of works from the Museo Reina Sofía’s collections. Is the past the path that leads to the present, or does its memory offer mistakes and paths of no return when faced with a future still to build? Or better yet, how does one travel back to the past from the present? The work of a national museum is not to reinterpret the past in search of a mirror for today’s society, but rather to let the concerns of the present find a multitude of responses in the past so as to understand that the present day is not something to be taken as a given, but rather as a becoming that is indispensably constructed as a collective.In uncertain times, it is not a question of imagining futures, but of trying to recognize in the present those desirable futures that are already here.

Contemporary art arose as an order of representation, a transformation of culture and the history of ideas, emerging as a systemic critique of modernity. Its development happened in parallel with a number of sociohistorical changes, beginning in the late 1960s and continuing to develop to the present day. Countercultural movements broadened the boundaries of sensibility and taste, giving rise to new counter-audiences. Second-wave feminism shook masculine domination, sending ripples throughout the gender system as a whole and making the representation of the body a siteof conflict. Environmental awareness began to highlight the problems of unchecked development of production processes andextractivism, with its global consequences and exponential risk. The decolonization processes of countries in the global South changed not only the world’s political geography but also its demographic flows over the last fifty years.

This floor provides a number of approaches to contemporary art from Spain. Since the 1970s, when the slow, collective construction of democracy began, Spanish society has evolved toward aboundless diversity in which art has played a fundamental role. Historical temporality is never uniform nor linear, but is rather made up of a series of complex processes, often presaged, often disjointed in time. Thus, this presentation features anachronisms and the coexistence of different moments, following three routes that return over and over again to the 1970s. Similarly, local geographical space is not a closed context, but rather a site of intersection and circulation of cultural manifestations. The Museo Reina Sofía’s intention is to share these stories as possibilities and as working tools for future presentations, so that the collections can remain permanently open to renovation.

Sabatini Building, Floor 4. Introduction

Itinerary I

A History of Affect in Contemporary Art

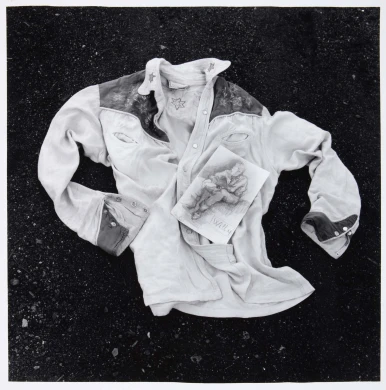

Pepe Espaliú, Sin título (Tres jaulas), 1992

Museo Reina Sofía. Fotografía: Roberto Ruiz

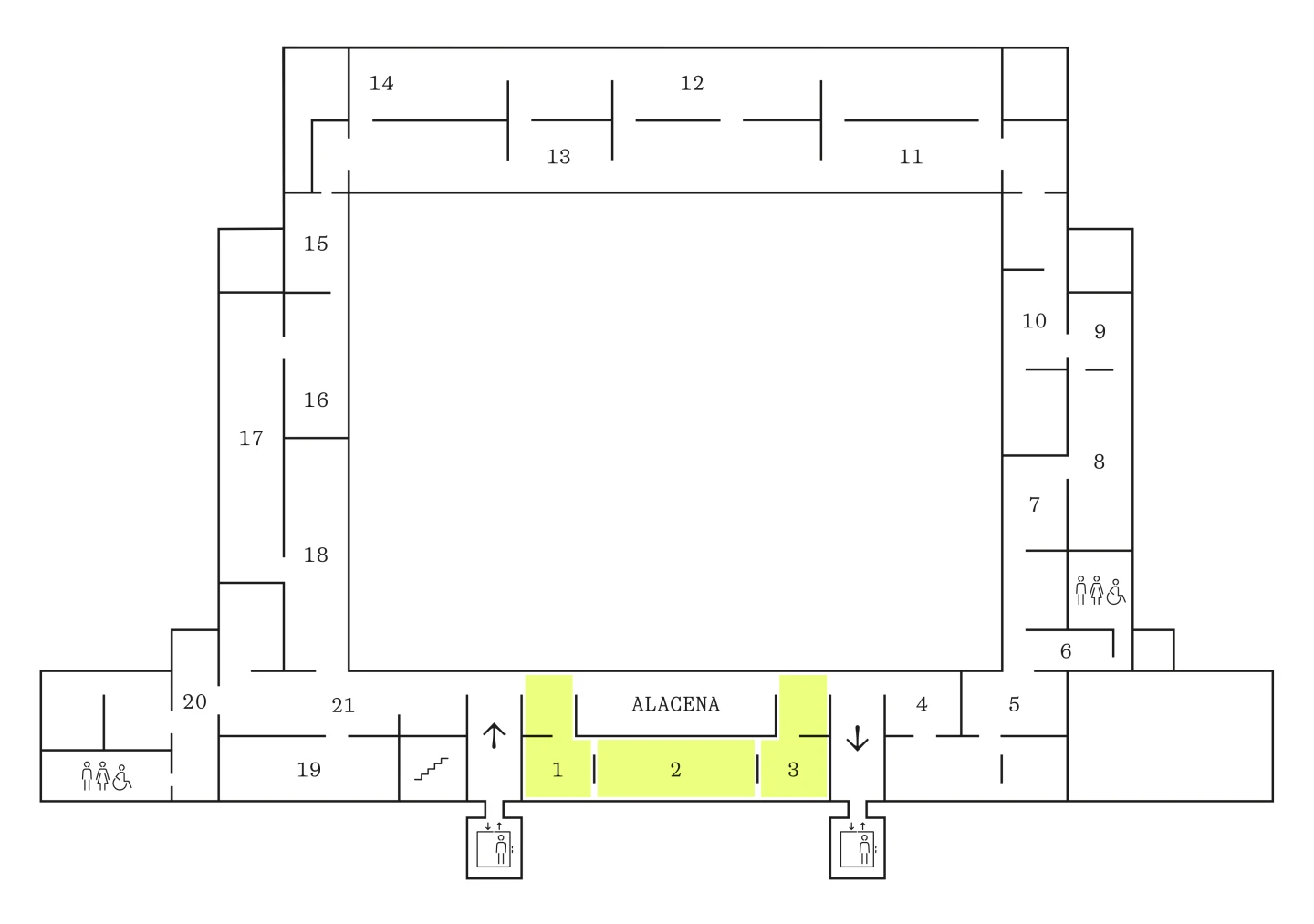

In an era of extreme emotionality, the public exhibitionism of social media, and the blurring of boundaries between fiction and reality, affects are central to the production of meaning. Affective systems were crucially important for the first generation of conceptual artists, especially those creators linked to international second-wave feminism who brought women’s bodies into the public arena as the site for their work on representation.

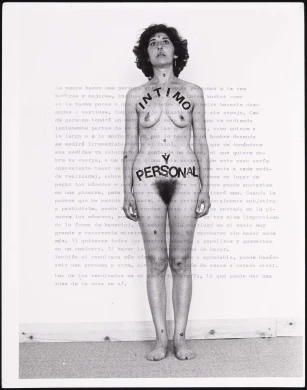

The new social presences in the 1970s also saw the emergence oflikewise unexplored affective relationalities, especially within society’s seemingly marginal spaces. The loving uses of the new sexual freedoms, thesystems of meaning that construct different subcultural communities, the intensity of new psychoactive substances and their addictions, and the proliferation of a shared, global image culture in late capitalism have had profound effects on the languages of art.

In the mid-1980s, it was the AIDS pandemic, which hit Spain at the same time as a heroin epidemic, that shook the system of affects to its core. Grief, no longer felt individually but collectively, shared by groups of people who were complete strangers, became the norm of social experience. The world order transformed in 2001 by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the related Madrid bombings in 2004 produced a new reality in which fiction seemed to have triumphed over the real. And yet grief is a stubborn emotion and an especially useful tool as social glue; it can perhaps remind us of the purpose behind what unites us as a society.

Featured Artworks

Sabatini Building, Floor 4. Itinerary I

Itinerary II

The Powers of Fiction: Sculpture, New Materialisms, and Relational Aesthetics

![Vista de Sala 11 «Estructuralismo escultórico en los años setenta». En primer plano: Juan Navarro Baldeweg, La mesa, 1974-2005. Museo Reina Sofía. © Juan Navarro Baldeweg, VEGAP, Madrid, 2026. Al fondo: Anthony Caro, Table Piece CCXXXII. The Dance [Pieza de mesa CCXXXII. La danza], 1975. Museo Reina Sofía. © The State of Anthony Caro/ Bradford Sculptures Ltd, 2015. Fotografía: Roberto Ruiz](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/styles/large_landscape/public/Colecci%C3%B3n/coleccion-planta-4-sala-11.jpg.webp)

Vista de Sala 11 «Estructuralismo escultórico en los años setenta»

Fotografía: Roberto Ruiz

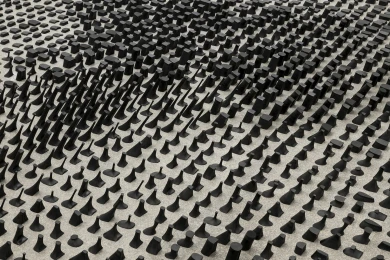

In the 1980s, as contemporary art expanded its affective capacities, it recovered a material condition that had been growing exponentially in previous decades. The primary affective sense is touch, and if each artistic period has its own overriding sense, this one is tactile, giving primacy to things and bodies. Objects are networks of relationships at a moment in time, crystallizing sociohistorical relations of production. Bodies are links for those relationalities. So isn’t the exhibition space a reality expressly designed for the encounter between bodies and things, in which to make those relationships legible and historical?

This route is a sculptural gallery. Sculpture physically coexists in the same space as the visitor: it breaks down the barriers between fiction and reality. The new Spanish sculpture of the 1980s had an enormous international impact, especially through female artists such as Susana Solano and Cristina Iglesias. In recent years, a new generation of young female sculptors has again come to the fore internationally, representing the most significant contribution to present-day Spanish art.

This path through the gallery empowers the visitor: to perceive transformations in the logic of the world’s objects and their relationships with people; to experience sculpture’s undeniable performativity, readable only in the act of moving beyond a singular perspective; to glimpse new materialities, forms that are still emerging and even speculative; and, lastly,to imagine fresh institutionalities through sculpture thanks to relational aesthetics, a set of artistic practices that require a community’s participation in order to be carried out.

Featured Artworks

Sabatini Building, Floor 4. Itinerary II

Itinerary III

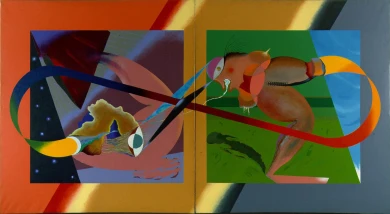

A New Framework: The Institution, the Market, and the Art That Transcends Both

In the early 1980s, work began on building an institutional cultural fabric that sought to combine the living memory of the return from exile withthe international context. The Museo Reina Sofía was founded as an art center in Madrid’s former Hospital General de San Carlos in 1986.

The emergence of a new and aspirational taste, the effects of institutionalization, and the opening of a new market resulted in unequal attention being paid to different artistic disciplines. Painting reached a pinnacle of critical enthusiasm in the late 1970s, culminating in a commercial explosion of its expressionist facet in the 1980s. Video art was nurtured in independent circles and its entry into institutions came late, but it sparked a renewal in forms of audiovisual production. Photography grew as a medium in both publishing and exhibition formats throughout the 1980s, becoming the preferred tool for revealing the constructed nature of reality in an image culture.

As the 2000s progressed, the translation of conceptualism into criticism of representation consolidated the figure of the multidisciplinary artist, treated ironically in Carles Congost’s video that tells of the exploits of a soccer player who decides to abandon the sport to become a video artist. The symptoms of a need for renewing tradition and rectifying flagrant omissions in art history also serve to expand the boundaries of convention. As democratic institutions, museums respond to the efforts by new social presences to gain visibility within a contemporary art that was shaped by the identity-based conflicts that ravaged the twentieth century and that are III becoming a central aspect of social coexistence in the twenty-first century.

Featured Artworks

Sabatini Building, Floor 4. Itinerary III

Room 15

Institutional Genealogy

Room 16

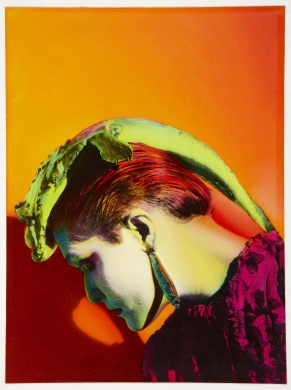

Videographic Cultures of the 1980s: The Sublime Image

Room 17

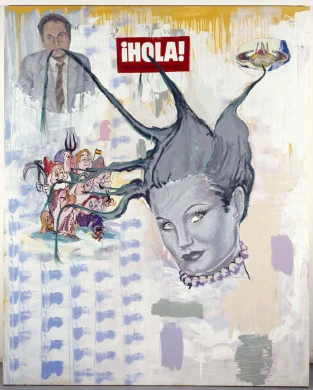

A More Painted Painting

Room 18

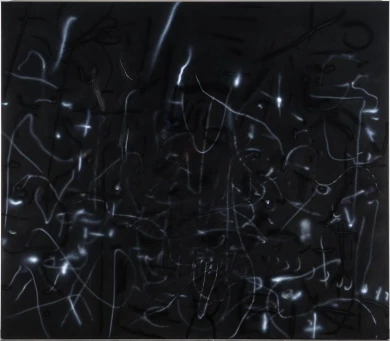

Art and Reality in 1980s. Photographic Cultures

Room 19

Critique of Representation

Room 20

“Lo afro está en el centro” (The African Is at the Center)

Room 21

Gender Practices: Social Choreographies for the New Century

13 may 2026

7pm

Lecture by Manuel Segade

Collection. Contemporary Art: 1975-Present

Mediation

(In Spanish)

COLLECTION 15’. Where Do I Start?

Mediation in rooms for the general public

The Main Site

Sabatini Building and Nouvel Building

The Museo’s main site has two access points, the Sabatini Building and Nouvel Building, both of which are the starting point of your visit and enable you to familiarise yourself with the different floors and exhibition rooms. Location and access.

It is recommended entering via the Nouvel Building (C/Ronda de Atocha, 2) if you have already purchased your ticket online.

Visits during free opening times are only for individuals.

Free of charge days

April 18, May 18 and 22, October 12 and December 6.

Public Holidays

The Museo is closed on 1 and 6 January, 1 May, 15 May*, 9 November*, and 24, 25 and 31 December. *These days may vary depending on the Community of Madrid’s business calendar.

Access to the Collection and temporary exhibitions

Audio-guide + access to the Collection and temporary exhibitions. Only available at the Ticket Offices

Audio guide to the Collection on Floor 2 (early avant-garde movements and Guernica) and the Maruja Mallo. Mask and compass exhibition for mobile phones + access to the Collections and temporary exhibitions.

You also need a ticket during free admission hours. You can book it online

For under 18s, the over 65s, students... Only available at the Ticket Offices. Check conditions

Visit the Museo today and return for a second time within one year