Hi. I'm Magz Hall, I'm a sound and radio artist, and my practice has been going for about 25 years, and I've been focusing on radio for the last 20 years. I specifically became very interested in Radio Arts when I got involved in 1997 with the first RSL, which was a restrictive license broadcasting for a month in London at the Southbank as part of the Meltdown festival.

And this was the first incarnation of a station called Resonance FM, which is to be the first experimental radio station in the UK.

And there, being involved in that station, I got to hear the huge range of radio art from across the world, in fact. And I was particularly excited by the work of Gregory Whitehead in the way which he played with radio and used it as a kind of dramaturgy to talk about its industrial relationship with sort of war machine and also with sort of state control.

So, it was really exciting to sort of have hands-on experience of broadcasting across London and thinking about an alternative way to present work on the radio.

In about 2002, I set up Radio Arts primarily to help fund the radio show that I was doing, which was a more conventional musical art show.

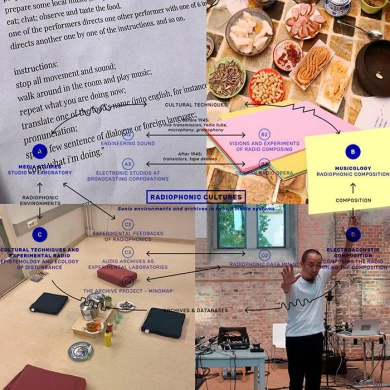

But I also had a vision of trying to get funding to help commission radio art pieces, because at that point, well, as most people know, community radio is a voluntary way of getting on air. So, no one's being paid. And I thought it was, you know, a real issue that artists weren't being able to be commissioned to make radio art. So, I did a project called Dreamland, which enabled about 15 artists to get aired on about 13 different stations. So that was kind of my first forays into thinking about radio art, and obviously there were different specials that got made on Resonance, which had a radio art leaning.

In 2003, I did a MA in Radio Production—management—and I decided at that point that I'd like to look into the experimental side of things even further, and I was offered a chance to do a Ph.D., a practice based on in radio arts. So, I thought that was a fantastic way of getting back on track with my sound art practice as well, which I've been doing again since 1998. And at that point they had been a mix of radio and sound art works. But I specifically wanted to look at 100 years of radio art and feed that into my own work.

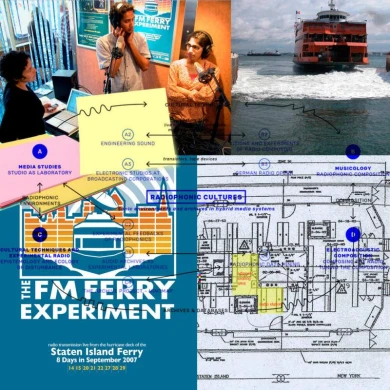

So that's exactly what I did. So, I did a project called Switch Off, which is basically looking into the possible futures of FM radio, thinking about who'd be squatting the airwaves, what would be out there if the FM was no longer used for commercial community or any kind of state sanctioned radio. So, I had a lot of fun with that and there was a lot of different kinds of stations that, you know, and I think I did about ten different stations which were either done as installations, actions, interventions…

One of the first ones was a radio station called “Numbers”, which was a homage really to number stations, but also was using tweets from the Occupy movement and turning them, you know, encrypting them, so they now became a coded message by numbers because it's, you know, one of the things I was interested that point was the fact that a lot of actually this was saying, yeah, the Internet is no longer a place to communicate.

And really, the only way that people can have any kind of private conversation was to go down the encryption line. So, it's kind of imagining in the future that we might go back to the kind of Cold War number stations where people will be sending encrypted messages via the radio, hopefully so that no one could tap into.

That piece was done as a mini transmitter surround piece. So, I had six transmitters and six voices and it became quite a Hadean piece actually, because each one was reading out the messages as numbers, and then it worked really well as a kind of composition. So, you'd have each, you know, each radio had a different transmitter playing the voices, reading the numbers, and it was kind of…, it had quite a musical quality to it. So, I would say it was a kind of chance composition and I was really pleased with the outcome of that.

Another of the “trace stations”, as I called them, was a station called “Radio Mind”, which again came out of my interest in religious radio. There's a lot of pirate stations in London which broadcast religious content, and I was now living in East Kent where really there are no pirate stations at all and kind of quite missing them actually. So, I thought it was good to imagine what kind of pirate stations might be on there. So, I made the spoof Religious Pirate Station, which I had as an installation at the Old Lookout, which is a tiny kind of fisherman's heart next to the sea in Broadstairs. And I had a microtransmission there where I had set many of about 20 birds, which were bird radios. So, radios that looked like birds up in the fishing nets broadcasting, minibroadcasting, microbroadcasting the piece.

And then, I had a 1920s radio which is made out of very similar wood to a lot of sort of more conventional Anglican churches. And had a giant cross made out of valves in the space as well. So, it was very much an uncanny situation.

And I look back at the history of radios from 1920s, and I was kind of excited by the way Du Vernet, who was an Anglican archbishop who was based in Canada, had talks about radio being a form of telecommunication and he was tapping into the spiritualist movement that was happening at the time where people thought the radio was magical and a way of communicating with loved ones.

The piece was really reflecting on some of those thoughts, and I also was interested in David Burliuk, who was a Ukrainian futurist who talked about radio modernism and this idea that, you know, that the radio waves were everywhere, and this could be a form of expression in paintings. So, I kind of tapped into some of their writing and then made some of it my own by writing my own script around it, and had great fun make putting together Radio Mind, which is this spoof religious radio station, imagining that as a possible future. So, you get the idea, each trace station was a very different concept, thinking about possible futures of radio.

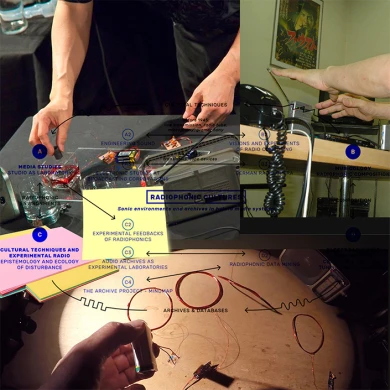

And after I finished the Ph.D., I had been running a series well, during the Ph.D., I was running a lot of radio workshops, helping others make radio, or having a go at transmitter building and every kind of project that I did, I kind of did a workshop around that and I learned a lot, quite a bit about transmitter building. And because I'd also been learning about how to make foxhole radios, etc., I saw that you could put transmitters into breadboards, so I realized I could build a transmitter straight into a tree, for instance. And that's where I got the idea for Tree Radio, which was to make a living pirate station, a station broadcasting, broadcasting the trees’ reaction to light and water. So, I worked with Anthony Elliott at Yorkshire Sculpture Park and we put together an installation up there of Tree Radio, which was really a tree broadcasting itself, you know, what was happening to it in real time on FM for a year, which was quite fun, it was a micro broadcast. And after that I got asked to make a work around ash dieback. So, I made transmissions spores, which again put a transmitter into a tree that was affected by ash dieback. And I listened to and cut up the discussions about how the spores are transmitted, which is quite radio like, actually. So, the piece was kind of like a, almost like a mini numbers station, just about the spores spreading from, from the tree itself.

So, I had this kind of double interest in sort of radio technology and art for the environment, which has definitely been a key theme in my work. And I've wanted to sort of, you know, move with that as much as I can so my current projects have actually been around air pollutions.

It started with the project I did at the Waterman's Art Gallery where I was looking at air pollution around that. And in that particular case I was looking at pirate radio in the Heathrow area, but I was also thinking about air pollution in terms of the flights that were going over. I was listening into those flights, so I made a piece last year with Peter Coyte, which was called Don't Listen Up. And we basically wanted to document the air, sea and land pollution that was happening all around us, particularly me, because I live right next to a landfill site which was spewing out methane gas. So, I was able to get field recordings of the methane gas going out. And also, in the installation I had the scanners picking up the air flights that were going over us in Whitstable.

It is on three or four major flight paths, so there's lots of overt air traffic that goes across the Kent region. And Peter had a hydrophone, he's listening in to the sewage pollution that has been affecting us a lot in the last few years in the UK. So, there's a lot of sewage in our rivers and seas, which is very concerning. So, you can hear that I've had quite an interest in sort of trying to make visible the invisible pollution that's been happening around me.

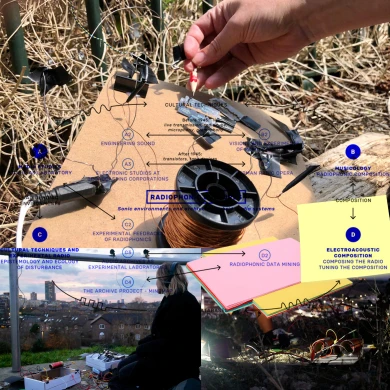

And this summer, that took me to the Pyrenees to run a radio camp. Andrew O'Connor, who's a fellow sound artist in Canada, who runs a pirate radio station and a show, asked me to help him co-run a radio station, a camp for a week, which is a great opportunity to think about this in a hyper local context, because it is, wherever you go, this kind of doorstep pollution is happening even up in the Pyrenees, which is a beautiful part of the world. There's a same amount of microplastic in the air as there is above Paris, which is actually very, very shocking. So, I made a piece called Long Wave with the participants. I was able to tell about our work and the project I'm currently doing and to make a little more broadcast ourselves around this, the pollution issues that were happening in the Pyrenees.

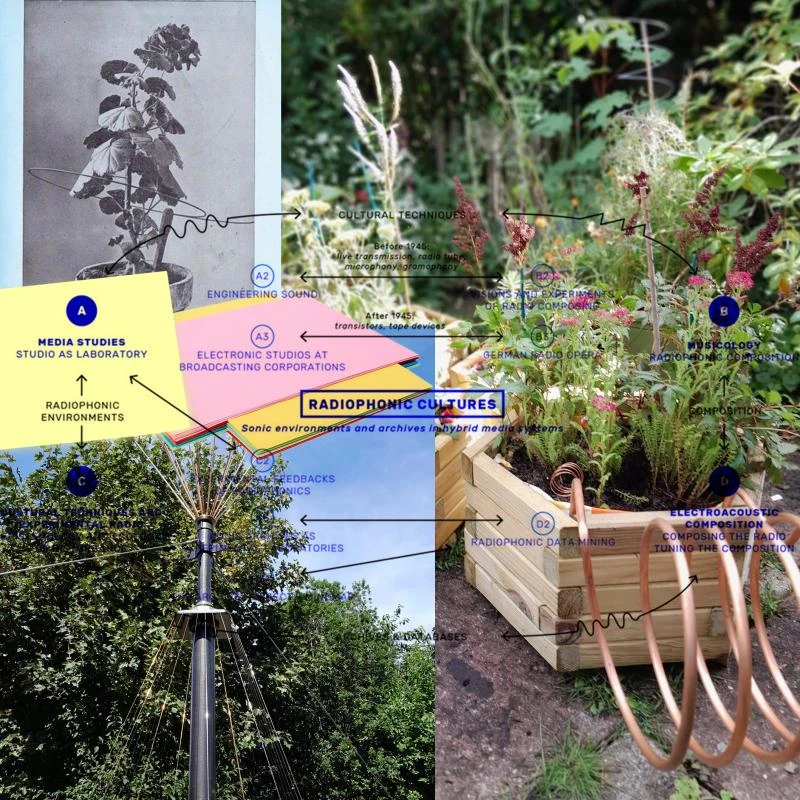

So, these pieces I've made recently are going to be going into my current project, which is called Radio Air Garden and for many years I've been thinking, oh, I'd like to do radio… God! But how are we going to do it? And suddenly last year I had the brain flash that I wanted to talk about air pollution and use plants that absorb pollution in the radio air garden. They’re also good pollinators. So, I've been growing some of those plants this year to see which ones look best. And I've been using electro culture techniques, which is a way of growing that came out in the ninth, sort of about 100 years ago, actually… A lot of it was being done in France, but it was international, where people would use antenna like coils to help things grow.

And some of the structures were very radio-like, so, I was really interested in this little sculptural side of this because obviously I was wanting to make a piece that embraced radio, but I also wanted to get a little way away from actual live radio and the electronics. So, I was very interested in the sculptural-like qualities of radio circuits and radio antenna, etc. So, these different projects have come out of that.

And so, I contacted Henry Dagg, who's a local sound artist too, he is very good at making musical instruments out of metal. And I thought he would be a great person to get involved in this, to help make a prototype for an aeolian harp, which was based on this very early electro culture antenna, which had a kind of guide-light properties. And I could see that that would actually lend itself quite well to an aeolian antenna. So, when the wind could play it, when it wasn't plugged in, speeds act as an antenna or to act as a receiver. So almost acts as an aerial, really.

So, the project I'm currently working on is Radio Air Garden, this whole year has been and since September last year I've been just looking into the 100-year history of electric culture and then thinking about the plants that absorb pollution and then thinking about, and then making pieces that could be add in the Radio Air Garden. But I also see it as a portable garden that can be taken to many different places and can be used for a kind of way of communing with others around radio jams, as well as playing pieces and picking up radio.

So hopefully next year it's going to be in Bristol for a while and if anyone out there listening and you want me to set up a radio air garden, do have a look at my website, it's magzhall.com. And you can read about all the projects I've mentioned, including the Radio Air Garden.

Now I've been asked to think about what's the future of radio and that's really interesting to me because obviously all my research and all my work has been thinking about, well, what's the future of radio? Where is it going? You know, I think it's a very open playing field. We've moved from bespoke radio sets to devices that just pick up radio where and when we want, using whatever means we need. We're more, I say with some of the analog technology that allows people to the very, very basic electronics to make radios and receivers. And I think that, you know, radio, though it may seem to some of the younger generation, something they're not engaging with this time, they're using wireless technology all the time to pick up the stuff that they do like.

So, I think, you know, it's been said many times that radio is a really resilient mean, you know, form. And I think that's the case. And I think audio and radio is rather unique. I think, you know, I don't have a grand plan for how it's going to roll out, but if when things but we do know that in…You know, in war situations, it's usually radio technology that keeps things going and is, you know, it really is always going to be a backbone to communications. When digital goes wrong people still have to rely on the analog stuff that's there to tide them over.

So, who knows, it would be quite provocative to say radio will, you know, might outlive the digital, which I know most people would be like shocked to think of. But, actually, it’s an interesting provocation because there is a possibility that it could. But at the same time, I think radio and the fact that we are able to share and listen back and, you know, to radio in a way that we've never been able to before has actually made it more accessible for more people.

So, in in some ways, radio and podcasting and experimental radio has never been more open and popular and accessible. And I think there's more of an audience and an appetite for experimentation and new forms of radio than it ever has been. So, you know, I think the future is very bright, but that sounds like an advert, doesn’t it?

Anyway, yeah, so I'm, you know, I'm looking forward to exploring further into radio and into sound, but I'm also interested in where, in this expanded notion of what I call expanded radio, or where, how far you can expand and how far you can push, what is radio arts. And that’s something that's also interest, is also somewhat something I'm thinking about.