[Clip from Open Wave-Receiver piece]: “Open Wave-Receivers use found materials to create self-powered radio wave receivers that open access to the sounds travelling on the invisible electromagnetic waves surrounding us.

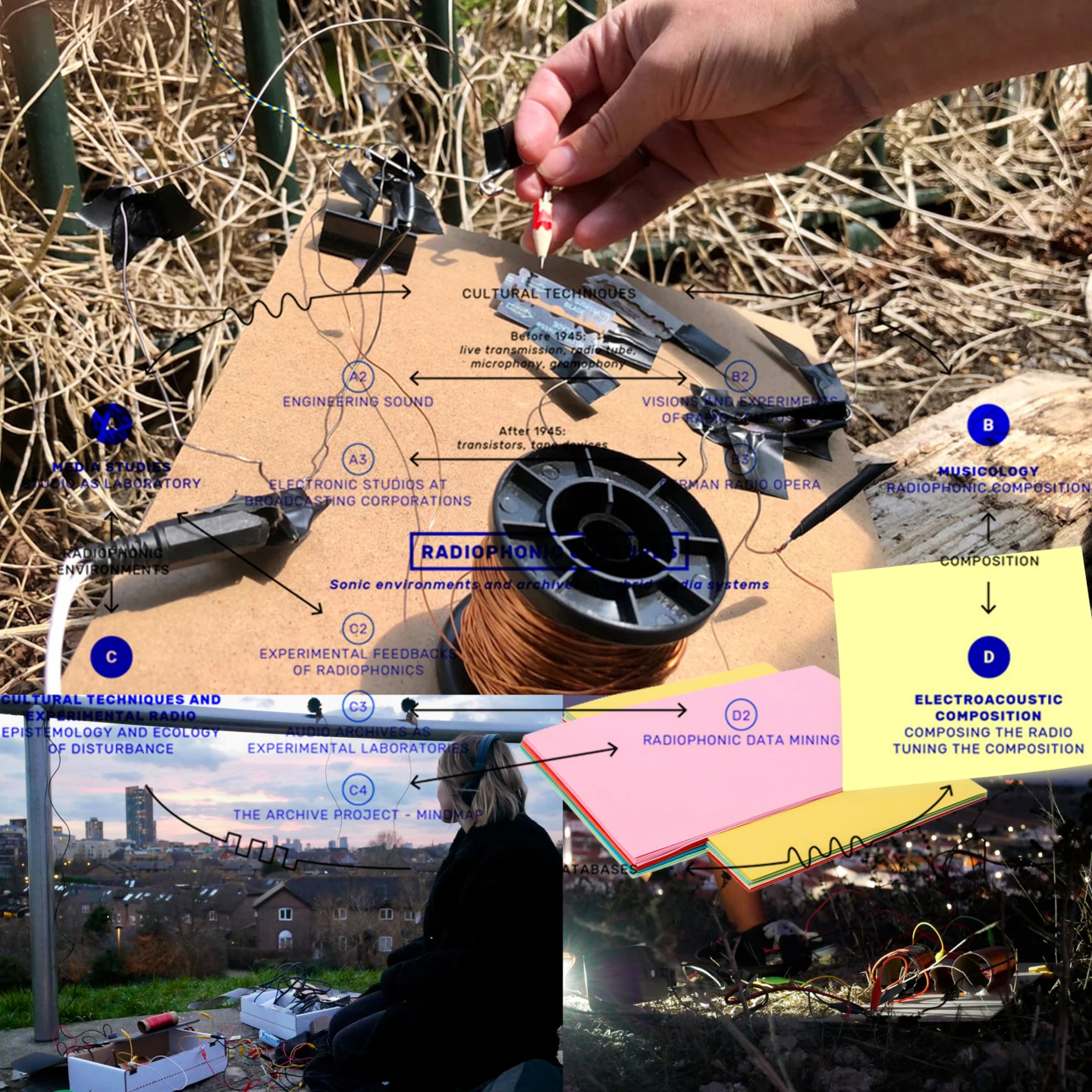

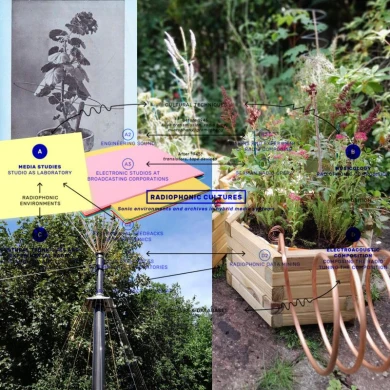

Making an Open Wave-Receiver will teach you how to construct a basic self-powered radio circuit that will allow you to have a very physical experience of radio. Over the past year, we've been making Open Wave-Receivers, experimenting with designs and sharing these experiences within our collective and with others in an open workshop.

Now we’ll share our methods of making and listening, so that you can hear some of this global electromagnetic network, and if you want, build your own self-powered radio receiver.

The Open Wave-Receiver can detect sounds that are invisible yet surrounding us; sounds travelling from distances near and far: data signals, talk radio, music, airplane navigations and sferics, which are bursts of natural radio that we hear when lightning interacts with the ionosphere.

[Sferics sounds]

The Open Wave-Receiver is not tuneable to a refined frequency. Instead, multiple signals from a broad spectrum of frequencies are received simultaneously.”

- Hannah Kemp-Welch: Hi, this is Shortwave Collective. My name’s Hannah Kemp-Welch.

- Lisa Hall: I’m Lisa Hall.

- Georgia Muenster: And I’m Georgia Muenster.

- Lisa Hall: So, we are three members of the Shortwave Collective who happen to be in the same country and the same room, all together at the same time, which is really exciting.

- Georgia Muenster: It is a rare experience.

- Hannah Kemp-Welch: We've been asked to introduce our work in relation to radio. We’re called Shortwave Collective, but we really work with all the different ranges of the radio spectrum. We like to think about radio as an artistic tool that we can use in different ways in our work. So, we use radio waves themselves as a sort of medium as well as a method to communicate.

- Lisa Hall: Yeah, our working as a collective with radio is as much present in the workshops that we do with other people or in artworks where we make sound compositions or sonic artworks that are shared, as well as just in being a collective and working together and meeting online once a month to talk about radio and the creative uses of it. - Hannah Kemp-Welch: Should we maybe talk about some past works, so we can talk through the past two pieces that we've worked on?

- Georgia Muenster: Sure.

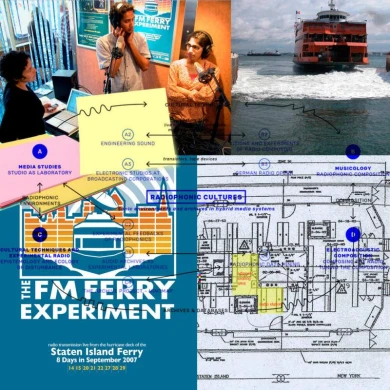

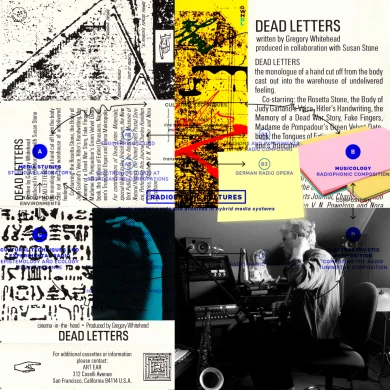

- Lisa Hall: Sure. So, one of the last works we did was called Constellations of Listening. This was a 22-hour radio broadcast playing out on Radio Art Zone. The work we made for this was 22 hours of us all going out in our own locations around the world and listening to radio waves with different radio devices.

[Clip from Constellations of Listening]: “It's about 14:35 in the afternoon. I'm back on my balcony listening to the signals coming through the walkie-talkie.”

This included Open Wave-Receivers. So, the very DIY radios we make ourselves, as well as pre-made radio devices such as shortwave radios, FM radios, walkie-talkies or maybe homemade VLF antennas.

We recorded huge amounts of listening experiences, where we were listening to different radio signals from broadcast radio stations, to natural emissions of radio from lightning strikes, or to data packets being sent and to be listened to by computers. And in each of these recordings, we often described to the listener where we were and how we were listening. If we were listening through a fence, if it was the end of the workday and we were tired and listening grumpily, if our hands were maybe moist and that was affecting and contributing to the radio recording. So all of these were the various different constellations of the listening experience, along with the time of day and the geographic location. And that work is now playing out on a couple of different radio stations once a week, including Resonance FM on a Saturday night, which you can listen to online.

[Clips from Constellations of Listening]

- Hannah Kemp-Welch: Prior to that, we designed what we call the Open Wave-Receiver. And the Open Wave-Receiver was a way, really, for us to get to know each other through a collaborative experiment in trying to work through different models of radio circuits. So we looked at some early designs for radios, and we tried to learn about the different elements which are needed within a circuit in order to receive radio waves and amplify them. And we started to think about what the simplest possible way to construct this radio circuit was and the cheapest possible way. And to communicate this in an accessible fashion, to really open out the physics of radio and to applied learning.

- Sally A. Applin: I'm Sally Applin. I'm an anthropologist and conceptual artist, and I'm interested in radio and specifically in sound recording and listening. It's part of my practice with ethnography for the work that I do and the research that I do. But I also am captivated by the art form of the process of listening, and I feel really lucky to have found the Shortwave Collective and joined them to explore that.

- Alyssa Moxley: I’m Alyssa Moxley. I'm an artist working with sound, using a lot of field recording. I’m interested in place and the emotional residence of a particular place and how we can hear history and memory or just our present-day relationship with that place. And so radio, I feel like, is a really essential part of listening.

- Maria Papadomanolaki: I’m Maria Papadomanolaki. I'm an artist working with sound and transmission, including radio. I’m based in Greece, in Crete.

- Alyssa Moxley: When and how did the relationship with radio come about?

- Sally A. Applin: For me, radio… I just love radio. I love the randomness of it. I love that it changes geographically depending on where you go, how you use your signal, what you use to catch it and listen to it. I love that people could stretch it and play with it in new ways. I love that people can subterfuge it and squeak in between frequencies or hijack frequencies to broadcast things. I love that it surrounds us and we can't see it or hear it unless we're kind of using, building something to tune in. I just find it to be kind of the track of humanity, and I really love it for that, too.

- Maria Papadomanolaki: I think it's complicated. As with Sarah's reply, it's an equally complex reply on why and how this whole relationship with radio comes about. Of course, from an early age, especially back in the days when I was young, radio and cassettes were the main, you know, access to culture here in Crete, where I grew up, and especially radio and some specialized radio shows. So the enthusiasm and the relationship, the accessibility, to this culture was via radio. Later on, as a student, I participated in the student radio stations as a producer, as an organizer, as a curator. And later on, as I became kind of like a full-time artist and researcher, a big part of my research was about transmission, experimentation with radio, with network audio.

There are a few instances where I used radio to create sound installations, sound interventions, improvise with musical ensembles. I've been part of SoundCamp for many years, where we've been mixing a 24-hour broadcast called Reveil. I worked with Wave Farm, when I was in New York; so we researched and we published the Transmission Arts publication, basically presenting different artistic practices that use the electromagnetic spectrum as a creative medium, and so I've been using transmitters to do all sorts of creative projects, and researching on transmission generally is an interesting area and I've written some articles about it and it continues to be a part of my practice, my research and my mentality, of my thinking about what creative practice might mean. That's one of the reasons that I joined the collective, the Shortwave Collective, as well.

- Alyssa Moxley: I'm really interested in radio because it allows for simultaneous spaces to be felt, to be embodied, and you're experiencing another location through listening to it, but really in a very physical way through these electromagnetic waves. It's really electromagnetism which is interesting for me and how we're able to use it for signals, how we're able to experience it as a physical phenomenon, listening to natural radio and things like that.

When I was in Chicago, where I was able to do a course on radio making with Brett Ian Balogh, I learned about building microtransmitters with the Tetsuo Kogawa model and also television transmitters. And learning about the physics of radio, which I found really fascinating and continue to look into.

[Tetsuo Kogawa in an extract from the Natural Radia performance]

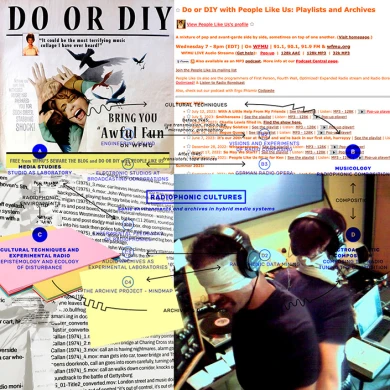

With Shortwave Collective, really everyone in the group was interested in some way in radio and it began with Hannah Kemp-Welch running a workshop on listening to shortwave radio. She was talking about amateur, ham radio operators and the culture of ham radio operators being very masculine, with the letters OM referring to old man, YL referring to young ladies, this, like, very patriarchal division of the role of authority and non-authoritative people in this listening relationship.

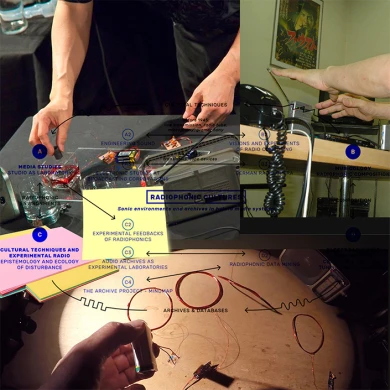

We also were listening on the web, not just through our own physical ham radios. We were exploring different methods of listening. We were doing some experiments around the foxhole radio, which is a very basic radio circuit that was used by soldiers in World War II to listen to the radio, and we started making a version of this with copper coil, a diode, which traditionally in the foxhole version was a razor blade, a burnt oxidized razor blade with a pencil, also a listening earpiece, a crystal radio earpiece. So, this was the beginning of a big project for us, which we did a residency about; some people attending online, some people in person.

There was an article in Make: Magazine describing how we made this circuit, which we called Open Wave-Receiver. And this is a very physical, permeable object. You can trade out different objects for the diode. You can use sound pieces of metal. One of the members, Brigitte, had discovered that a certain brand of tent-peg metal alloy worked really well as a diode. We were also using galena, and taking out this sharp razor blade aspect. And using this Open Wave-Receiver to just listen to anything that came through it, and it was really connecting our bodies with the physical location, with the objects that we were finding.

- Alyssa Moxley: Amateur radio and radiophonic data timing, the use of amateur radio, collaboration with different communities, uncovering the intrinsic workings of radio through education.

- Sally A. Applin: So my research, a lot of my doctoral research, was in the maker community and people that are creating and making things outside of what you'd find manufactured. And I had formed some relationships with Maker Faire and the maker community over the years, and as the Shortwave Collective was starting to produce their Open Wave-Receivers and trying to communicate how to replicate those, I thought it might be interesting to ask Make: Magazine, which is kind of a branch of the Maker Faire community and maker community, if they might be interested in an article that we could create, where we could publish it more broadly and expose more people to this type of radio-building. Make: [Magazine] has actually produced several or a few articles over the years on foxhole, what they call foxhole radios or how to make a radio. But the thing that they hadn't done was talk about it from a feminist perspective, from a women's perspective. It gave them the opportunity to reframe how they thought about radio and making, and it gave us an opportunity to have our process organized and then printed and distributed to people that could get turned on by it and innovate with it.

The other thing I think that's really interesting about the making community, as well as how it spills into the amateur radio community — which was also part of my doctoral research — was just the variation in pieces of things that people are into: some people are really, really into building antennas, some people are into collecting data and looking at patterns, some people are into distance and how far they can listen. So, there's something for everyone in amateur radio and in listening and in making. And I love that there's a broad spectrum and a place for all kinds of education and opportunity in this art form.

- Alyssa Moxley: I think in terms of the feminist perspective, in making the Open Wave-Receiver, you have to understand that it's sensitive, understand that it's reacting to the weather conditions, to the placement of where you're putting the antenna, to your own body, to the ground. If you have a good ground. It's not about finding one perfect, strong signal. Sometimes you are going to get a very powerful signal because it's just broadcasting very strongly in the area. Sometimes you'll have this overlapping of different signals. Sometimes it would be a kind of fading in and out. Or perhaps you'll hear some electricity. Sometimes people have heard the VLF, very low frequency, natural radio sounds of lightning in the ionosphere, all of these different things that could be happening simultaneously or one at a time in the Open Wave-Receiver.

And when we're building these things, we are making space for an experience, for an open listening experience, where it's quite different from a traditional use of radio, where you're tuning in very tightly to one channel, when you're searching out a particular frequency to listen to. Rather, we're kind of tuning into the environment and having this kind of broadband experience, which is limited by the objects that are used as the diode and the radio. It's limited by the length of the antenna. Sometimes we've attached the antenna to other objects in order to increase its reach. We had a project, Fencetenna, where we were using different fences in these different places.

Since we were working on this Open Wave-Receiver project and on this residency in Portugal, when we developed this Make: Magazine article explaining our processes and how to make it, we have also done a lot of workshops, a lot in the UK, in France, in Norway, and I think we have some work coming up. And we're working with different kinds of communities in building these Open Wave-Receivers: sometimes with local materials that are available in Portugal, where people are using cork board; often for wrapping the coil we're using bottles or sticks or anything cylindrical that we find; in France a lot of people had used these little toy animals with test tubes because of the objects that were available in that hacker space. In the UK, I know that there have been members of the group who have been working with communities with different learning needs, with deaf communities, with older generations and younger generations of people. And it's really about discovering this listening process and also discovering these basic elements that can be put together to receive radio. And I think a lot of people are very curious, satisfied, to see that it can be so evident. You can have all of the pieces there. You can hold all of these pieces and see how you can stick together a rock and a piece of metal, and you can listen to other places far away.

[Clip from Open Wave-Receiver piece]: “How to troubleshoot your radio. This kind of radio is powered entirely by the energy of the radio waves, and so the signal is likely to be very weak. You might not hear anything at all when you first assemble your radio. Don’t worry though! Wait til sunset, take your radio outside, climb a hill, and string your antenna up as high as you can in a straight line parallel to the ground — these are the conditions that we’ve found give the strongest signal. If you're still not hearing anything, look at a radio circuit diagram. Are your parts in the correct sequence? Have you stripped the ends of your wire well so that the connections are solid? Are all the needed parts touching, without any extra unwanted contact points? If your antenna is suspended in the air, change its position. Don't let your antenna wire touch the ground wire.”

- Alyssa Moxley: How do you see or think the radio of the future will be listened to?

- Maria Papadomanolaki: Okay, I'll try. I'll try and answer that really kind of like difficult question. Radio of the future. I think that radio in general has a futuristic quality to it, in terms of using the ether, the electromagnetic spectrum as a means to travel and connect people together. So, this type of understanding of how transmission can be a means of communication is something that has been replicated more recently through the interweb and network communities. So, I would say radio has been the future, has shown the way to the future. Now, to answer the question, is to say that I really believe that in the future there's going to be a breakdown.

[A phone rings] Sorry, it happens.

So, I really hope that in the future people will fold back more and more to practices that ask for this deciphering and breaking down bigger structures, and people will be more competent to use technology in a bottom-up way, more like what Shortwave Collective is, like making radios from, you know, used materials, from things that they can find within their homes. You know, it's very trendy now to talk about circular economy and all these things. I think this will become a reality of the future. I think, I hope. I believe that the radio of the future is really bottom-up. It's reversing, hopefully, the hierarchy of what transmission means. I think it's going to be very topical. I think what Kogawa was imagining or was describing happening in Japan, the micro radio boom, it will become hopefully standard. So, there will be smaller clusters of radio transmission for neighbourhoods, blocks of buildings, rooms. I don't know. It's going to be more guerrilla than it was, than it’s ever been. So, that's a very futuristic and optimistic view of the radio and its future. I don't want to believe that radio is, how to call it, an old technology. I think it's very pertinent. And there might be, for instance, some versions of radio that will be hybridized — lots of generations right now are into coding and into making things. I think we discussed about the maker culture a little bit earlier, and I think humanity needs to be more sensitive towards these types of understandings and practices in order to survive.

- Sally A. Applin: I actually agree with Maria. I think that the future of radio is a tension between a conglomerate of homogenized services like iHeart Radio and Clear Channel and Sirius, and like things that are condensed, consolidated, have acquired and siphoned up a lot of material and broadcast in just kind of a group way almost globally now, combined with the rest of us that are trying to listen and hear and put voices out in new ways, in smaller ways. So, it's this tension between consolidated, homogenous radio and heterogeneous distributed radio. And I think that while software has been growing in the use of radio — how it controls broadcasts or controls the machines that people use to develop content, or use software to create or control radio — it's tenuous to do that because there's always that chance that power will go out, software will go down. It creates a lot of contingencies and it creates a layer between people and listening. So, I also think that independent, pure hardware will have a very strong place in the future, particularly as energy needs change, as economies change, as climate changes. I think people will be just changing the way that they need to listen and communicate and rely on, as Maria was talking about, kind of those more basic materials.

So I just see it as this… there's room for everybody, but it is kind of this; it has been growing towards a more homogenous model and I think we're starting to see a reaction to that. I don't know where it's going to go, but I think software has been ramping up to be a big part of radio. I just don't know if the future is going to hold as much software as people think it will.

- Alyssa Moxley: Radio as FM broadcast has become perhaps less occupied. There becomes more space for radio to be used as an artistic medium because the qualities of the electromagnetic spectrum can be appreciated outside of utility. But for their aesthetic, for their malleability, just for the interest in their physical qualities.

Recently, when we did this workshop in Norway, we were listening to a couple of stations coming through. I don't know exactly what they were. There was a piece of music that was repeating all day. We listened to the same music both days and some voices coming in and out, perhaps from Pakistan, so maybe that was coming from quite far away. There's one FM broadcast station in Bergen, where we were, so there was room for other things to come through, smaller things, more localized things. It's interesting that we can have this very local dispersal, yet those local things, they can travel much farther than they're intended to, sometimes. It's very open and permeable. I also think it's interesting if we develop these small networks of broadcast radio that it can be intervened in — anybody can listen and, you know, perhaps anybody can interrupt if it's a small power situation. And I also think that is interesting. It becomes, it is, a very public forum. We think a lot about encryption and privacy and security, but I think it's also interesting to think about just encountering different ideas, encountering different spaces.

- Maria Papadomanolaki: Also the idea of listening in. You know, it's very trendy. Listening in to other people, like technologies and listening in, or people listening in to conversations. In this type of context, listening in becomes a way of accessing and participating, intervening and interrupting, so there's no secrecy in a way. It's kind of like reverse engineering, the model of, you know, keeping everything apart and keeping it secret and kind of like separating the source from the reception. It all becomes like kind of a unity of signals that are accessible, that can be picked up and, you know, interrupted at any time. So, that also kind of like encapsulates the idea of the fragility and ephemerality, of course, of these transmissions.

[Clip from Open Wave-Receiver piece]: “How to make an Open Wave-Receiver was created by Shortwave Collective, a ten-member international feminist art group founded in 2020. Collectively, we’ve been exploring the process of radio circuit assembly, considering the radio spectrum as an artistic material.

Shortwave Collective is Alyssa Moxley, Brigitte Hart, Francesca Casauay, Georgia Muenster, Hannah Kemp-Welch, Kate Donovan, Lisa Hall, Maria Papadomanolaki, Sally A. Applin, Sasha Engelmann. More information on our projects can be found at padlet.com/shortwavecollective/radio”.

Is There Really a Place on Radio for Experimentation?