Hello, my name is Torsten Michaelsen and I am part, a third to be exact, of a group which is called LIGNA.

LIGNA is a group of three people. My other colleagues are Michael Hüners and Ole Frahm. And we work already for quite a long time, for 20 years, on projects that understand their audience as a collective of producers that could gain agency to change a place or a situation.

In many of our works, we work with audio pieces that the audience hears and invite them to act or to follow a choreography, gestures, or of movements. So, this work, or our work, is related to this. It's related with audio and, to be exact, with radio right from the start. Because we met a long, long time ago at a… or in a free radio station in Hamburg, a port city of Germany, already at the end of the 90s. And the “free radio” is a concept which is quite, yeah, quite well known or quite often practiced in Germany, which means that it is a legal radio station, not a pirate radio station, but which is completely, so to speak, under the control of the people who are running this radio station. So it is really free to make its own content, certainly in the, in the realm that the media legislation offers to it. But yeah, they can really do their own program. And we finally, after a while, had a full frequency 24 hours a day and seven days a week. And we worked a lot at this radio station doing all kinds of broadcasts. For example, also many broadcasts from demonstrations where we experienced how radio could, yeah, intervene also in demonstrations. Sometimes giving people hints where they could meet, where there's not so much police force gathered and so on.

So, it was a great place to experiment with radio, these three radio stations, but we found out that there were not really many experiments also with the formats of the radio. So, in most places, or in most cases, people were just doing, content-wise, whatever they wanted to, but we criticized or we found out that in most cases the broadcast, the radio was simply used to distribute political reflections, but people were never really reflecting the medium, the radio itself. They were just regarding it as a kind of channel to their audience. Although the audience might be small, at least some people were listening. That was the belief of the radio makers, so that people were really closely listening what’s important for them.

And then they thought that the audience, the people who were closely listening, might act afterwards. But we, as a group, as this group LIGNA, were only listening to the radio. We were always understanding the situation of radio reception itself, the situation of listening as something which was already an activity in itself. And we wanted to work with that, with this activity. So, the idea was to bring the activity already into the situation of a reception itself, which thus became an activity of itself. So, the idea was to explore, to research on the situation of reception. So, right from the start we were not so much interested in the situation of the studio, of the broadcasting studio, and making a sound art there, but we wanted, we regarded radio art more or less from the start as a work with the situation of reception.

Our media practice, that of LIGNA, developed as a practical, and certainly solidary, criticism of what surrounded us, the media practice of the free radio station that was free in doing what they wanted to do but never were able to free themselves from the conventions of media usage. So, right from the start there would not be… The group of LIGNA would not even exist without radio and the specific context of free radio, which is certainly very different from, for example, what is called in Germany public radio, öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk, which also has its freedoms, but certainly relates on a big broadcasting company, big broadcasting studio, where you have your time slots maybe and where you could certainly also, at least in the night times, experiment with sounds, but certainly not with a situation of reception itself.

And the first format in which we tried to experiment with the media reception, radio reception, was called and is still called LIGNA's Music Box. It is a radio broadcast, a kind of request concert, where people are asked to phone in and not ask the radio station to play a certain song or something, but to play it themselves. We started this in the late 90s, a long time before exchange of music was possible on the internet and so it was really for some years a format for people to exchange music. So, they could call in, the broadcast always had a certain subject, that was very important, so people were always, yeah, already been guided to certain ideas, what they might play in the broadcast. For example, a subject might be the most scratched record which I have or compact cassettes or music of my elder siblings or break-up songs, for example, was a great subject. And then they could call in, talk a little about the song they wanted to play and then hold their telephone receiver in front of the loudspeaker and play the music they wanted to play. Certainly not in Hi-Fi quality, but that was not so important for us.

This broadcast, by the way, is still running on the free radio station FSK in Hamburg now for 25 years. And yeah, as I already said, it was a good way to exchange music and we also learned a lot about music so we were never really the DJ guys who have the coolest record collection at home, but also we were not we did not need that because our listeners were always playing very interesting stuff to us so we learned a lot of new yeah music genres also out of this radio broadcast.

And the broadcast was, and still is, not only about playing and talking about music but also an intervention into the everyday life of the listeners. At least, this is what we found out, and what was interesting for us in, yeah, making a theory about this broadcast, the listeners who became broadcasters for a moment. We realized that the situation of listening and participating in our broadcast was never a clean or pure encounter with the words we broadcasted. So, it was never the way the other people in the free radio station imagined the broadcasting and reception situation so that people were really listening to them. So, it was never a clean situation, but always, yeah, as we called it, a mutual contamination.

The radio broadcast intervened into a space, and the sounds of the space where fed back into the radio, so radio showed itself there, at least we found it, as a dirty medium, and exactly this dirtiness of radio so that sounds are intermingling and that that radio is contaminating with its sound a certain situation was interesting for us.

We discovered that radio broadcasts were never controllable, and they were always uncontrollable. Once you have broadcasted something, you cannot control anymore which relations which associations the words and sounds enter, what their effects are and what the and what might come back. So, we were never able to control what people were doing when they were calling in. This is the public space or for us, this is the public space of radio, and that fascinated us. So, we went on, trying to develop radio formats that played with the impurity, the dirtiness and the uncontrollability of the medium.

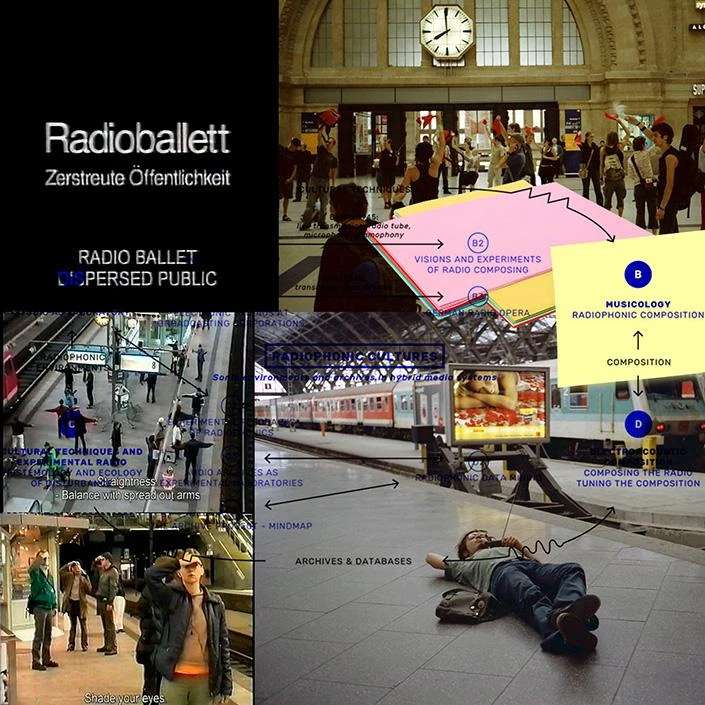

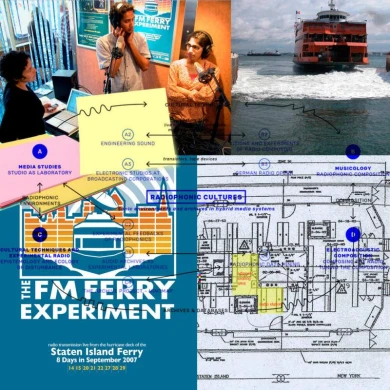

It was quite close at hand to experiment with the uncontrollability of the public space of radio in controlled, closely surveyed public spaces. So, to bring, so to speak, the public space of radio, this uncontrollable public space of radio into closely surveyed and thus, controlled public spaces. And so, the first bigger work we made was exactly about that. It was called the Radio Ballet and it's also already quite old. It was taking place for the first time in May 2002 in Hamburg, the city we were living in then. And we followed an invitation of the Kunsthalle, thee big museum, also modern art museum of Hamburg, which is quite close, luckily, to a very controlled space, the main station of Hamburg.

At that time, so in the late 90s, early 2000, it was a very contested space. Just shortly before we made the intervention there, the Radio Ballet, it was completely privatized, and many people due to this privatization, were not allowed anymore to stay in the main station, to stay at this place.

People who were, yeah, just hanging around, they're asking others for money, people who were did not have the intention to travel or the intention to buy something there. And so, the idea was to broadcast on the radio a choreography for radio listeners, that explores the threshold, the gray zones between the loud and the forbidden behavior, and the allowed and the forbidden gestures.

So, what we did was, we simply invited our radio listeners, so the people who were anyway. listening to the free radio station, and more than 200 came, many of them with their own radio receivers and headphones and we also bought a lot of cheap radio receivers ourselves and distributed them at the Kunsthalle to the listeners of our piece, and then we broadcasted on the frequency of our free radio station.

The radio broadcasted for one hour. People were spreading out all over the train station and then followed our choreography. And the choreography consisted of very simple gestures, instructions, so to speak, for very simple gestures. For example, spread out your hand in front of you, like when you shake somebody's hand, and then please turn it just 90 degrees so that the palm is directed upwards, like you were asking for money. And what was at stake there was that suddenly the very common and certainly allowed gesture of shaking somebody's hand was turned into a forbidden gesture: I'm begging for money.

Other gestures and movements that were broadcasted were just spreading out your arms and people were sometimes also asked to dance and so on.

And this choreography was interrupted every five minutes or so, also by reflections on the format of the Radio Ballet, how we call it the whole thing, dealing with many things, but for example, also with idleness. In our perspective, the Radio Ballet was a practice in idleness as people were mostly simply listening and not acting in the way they should act at the place. People who are simply doing nothing or just listening or doing things repeatedly like they were asked in our choreography. Many cases excluded from places like the train station unless certainly they are sitting in cafes and consume something.

So, the participants in the radio ballet, we said in the reflection part, were practicing boredom and boredom as a form of deviant behavior.

Consequently, the subtitle of the radio ballet was Exercises in Unnecessary Stay or Exercises in Staying Unnecessarily. This was a term which we took directly from the house rules which were banning “unnötige Aufenthalt” in German, which is “unnecessary staying”. So, the idea was to take something directly from the regulations and terms of reference and call the whole thing a kind of exercise in violating or subverting at least the house rules. Not very astonishingly, the railway company of Germany tried to prohibit the whole thing just days or a week before it was about to take place. They learned about the planned intervention. We invited people excessively by email, and one of the emails simply also found its way to the German railway company, and the whole thing finally went before court, where we were so lucky to win also because we had a really good lawyer who was very much into these questions of public space.

So, we were able to win the case, and this intervention of the German railway company convinced also the last people who previously thought this is just an art thing, performance art, not really political. But when they heard about the attempts of the German railway company to prohibit the action to take place, they were also convinced that there is something at stake, and so they also arrived. This was also the reason why so many people were there. And so, the Radio Ballet could take place, or could not be excluded, and it showed how political actions in surveyed spaces could look like. And our argument was always that the distribution of radio, which some people regarded as something to be overcome, that radio is only distributing and that it does not have a channel for real communication. And we said no, the distribution of radio might also be an advantage. The distribution and the fact that you could not control what happens out of it because it allowed people to distribute just anywhere in the train station and to really turn it during this performance in a kind of a little bit uncanny space because it was really a little bit like maybe in a horror movie where suddenly in every corner of the space, people were doing strange things.

We were able to stage the Radio Ballet in many places and in very different formats or forms in the following years. We made, for example, a version for shopping malls because shopping malls are certainly also a very interesting, controlled space. The idea there was to keep the whole choreography as subliminal as possible so that people realize the whole time, or that people outside of the performance realize the whole time, oh, something is going on here, but I don't know what it is.

But directly after the Radio Ballet and the main station of Hamburg, we wanted to develop or to go on and develop other formats of radio usage. And the next one, just really a month later, was the concert for 144 mobile phones.

And so, it was called Dial the signals! Radio Concert for 144 Mobile Phones and the idea was to engage the audience in the process of collective composing so we had these 144 mobile phones they were lying for a whole night in again Hamburger Kunsthalle so this big art space in Hamburg in the grid of 12 times 12 devices and a composer, Jens Röhm, who unfortunately is already dead, had composed ring tones for them so it kind of field of ringtones and he composed all of them certainly different. And the phones were lying there with this field of ringtones and the problem was that he could never really test how it would finally sound when many of these phones were ringing.

These phones, by the way, were the first generation of polyphonic ringtone phones in 2003. Was something very new. Above these phones, which were lying there on a pedestal, was a camera and two microphones. The signal of these microphones was sent to our radio station and from there it was broadcasted. So, people could listen to the sound of the phones, and they certainly only made sounds when they were called. So, they were asked to call these phones. In different ways or different channels, we distributed the number of these 144 phones to the audience, to the people, and they were asked to call them. By the calls, they were starting the ringtones of the individual phones and so they were participating in this collective concert.

The radio concert of 144 mobile phones lasted for 12 hours, from 8 o'clock in the evening to eight o'clock in the next morning, and consequently, certainly, it became more silent during the night hours, whereas at eight o'clock in the evening, where people were starting to call in and to trigger these mobile phones, it was certainly very complex and loud. Our idea was to invite the people to participate in the process of collective composition. You could listen to the concert to what already others were doing and then add something to it by calling a certain number and thus trigger a sound. But you never knew what others were doing at the same time when you were calling, and how the whole situation, how the whole field of sound was already changing in this short time span in which you were calling.

So, you never knew how your intervention was meeting with the intervention of others. So, you were taking responsibility for what you were doing, but you never knew in which situation you were taking this responsibility. The whole concept was also streamed on the internet, also something we were pioneering in these days for us. So, people were from all over the world who were able to participate in it, and the grid of phones was also visible on a home page in a kind of stylized form, but you could always see which phone was called at this moment and you could add then something to it. And certainly, people during the time also gained a kind of experience and got more and more experienced how phones that they called sounded like. So, the sounds were very different. Some were just doing one tone, some also kind of sequence of tones. And by also trying out how this worked, people gained experience and could play this concept, so to speak, more and more experienced after a while.

We liked that a lot. We were never able to repeat this concert because it was certainly a lot of effort to get hold of these 144 phones and also144 telephone numbers, quite a lot. Finally, I just wanted to mention a radio play, so we made many pieces in the meantime which are not directly related to radio, but just the last weekend, looking back from the day where I recorded this podcast, just the last weekend, we again really made a radio play. And also, a radio play which we wanted to do. We wanted to do already for a very, very long time. We wanted to stage the Lindbergh flight or the ocean flight by Bertolt Brecht.

You might know that it's a radio play Brecht and the composer Kurt Weil, and also Paul Hindemith conceived in 1929, so in the very early days of radio. And at that time, there was a vivid discussion of what radio could add to the concert and also to the theater because suddenly concerts were also taking place in radio, were recorded for the radio. And many people said, OK, but this is not really what a concert is about to be or how it should be because you're no longer sharing anymore the situation of the concert being played with the musicians. So, the audience and the musicians are in different situations, so to speak.

And people said that you could not really understand the idea of the musical piece, and certainly what a concert might be. That you are, in a way, gathering competence, listening competence when you just hang around, sit at home and listen to it in a row with other magazines and household advisers and so on. This was a big discussion, and Brecht and his composers intervened into it by suggesting to make a radio play where the listeners or where the piece is incomplete. So, the idea was to broadcast this Lindbergh flight. The story was simply the crossing of the ocean by Charles Lindbergh in 1927. So, the first person who crossed the ocean from America to Europe being alone in his plane. And the idea was to make a play out of this.

But the main role, the role of Charles Lindbergh is spared out. It is not broadcast and then people at home could edit. And our argument or our idea when we already theoretically dealt with this play was that people when they do it at home will not really complete this piece, but more or less underline that there is a kind of division, a distance between the broadcasting situation and the listening situation at home. Because they are never able to just consume and listen to the complete radio play.

What we did was we staged it in that way. We had a band, a wonderful band or small orchestra that were playing the piece and the audience was at another place standing in front of radios, communicating with the radio by singing and speaking, the role of Charles Lindbergh. Before they were in this room they were practicing a little bit with the band, so learning the difficult parts, so to speak; and then they went over to this other place and singing and playing and speaking with the radio.

Which worked astonishingly well, and hopefully, we will be able to repeat this again. Yeah, this was, in a way, a short trip through the way we like to play with radio, and how we think, yeah, how to thematize and to deal with the reception situation of radio, and what was also interesting for us in this last piece I mentioned was that there was no feedback, and so people were really isolated in the listening situation, and playing with the radio from the band. So, this what you might now understand as being very unmodern of radio, where there not a simple feedback like in the online media, was in a way underlined there. And we think, but this is just something one could discuss, that this might also be one of the utopias of radio when you are now realizing how especially social media could also drive people in complete madness and always confront them with their own effects and underline their own effects, their own hatred. Sometimes distance might be a good thing to practice, and in a way this was a kind of practice or exercise in gaining distance from the media you are receiving. So, this is certainly not an idea of the radio of the future but maybe an idea of how radio and situations of radio might be regarded as also a criticism of the media landscape right now, which is already very much different from the media landscape of 20 years ago or 25 years ago when we started our experiments. So, the radio of the future, we don't have really a concept for it. What we like very much are radio projects that link radio to a certain space. So, we worked a lot in the last years with a radio Aporee, a radio station so to speak, that is a kind of world map where you could upload your audio files.

Many people from the field recording scene do it and I think Radio Aporee has now 50 000 or even more field recordings from all over the world on this world map, but you could also make interactive radio dramas here, so pieces where you put your audio files on this map and then people could walk through them and when they stand or when they walk into the GPS coordinates of a certain audio point, then the sound is triggered and so you could walk from one point to the other and not even realizing and into which point you are running in this moment, and this is certainly a wonderful play of very site-specific radio or internet radio usage.