-

Thursday, 3 May – 7pm

Session 1

Second session: Friday, 18 May – 7pm

First session presented by David Cortés Santamarta, curator

Second session presented by Gérard FromangerGérard Fromanger and Jean-Luc Godard

Film-tract nº 1968 (1968)

France, DA, colour, silent, 3’Anonymous

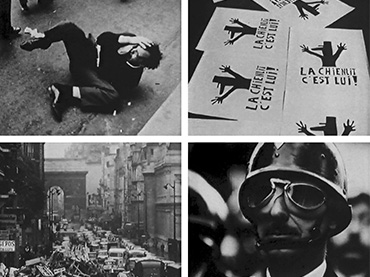

Cinétracts (Film-Tracts), 1968

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 76’The political pamphlet Cinétractez, handed out in May 1968, describes the cinétract in the following terms: “What is a cinétract?: 2’44” (that is, a 30-metre-long reel of 16mm film at 24 frames per second) of silent film on a political and social theme, or any other, aimed to trigger discussion and action. Through these cinétracts we attempt to explain our thoughts and reactions. Why? To: Oppose-Propose-Surprise-Inform-Question-Affirm-Convince-Shout-Laugh-Denounce-Teach. But with what? A wall, a camera, lamplight on a wall. Documents, photographs, newspapers, drawings, posters, books, etc. A marker pen, tape, glue, a tape measure, a timer”. This new format places the stress on both the will for political intervention, driven by the urgency of revolution, and an invitation, in the wordplay in the title, in a creative appropriation of this approach to film.

-

Friday, 4 May – 7pm

Session 2

Second session: Monday, 21 May – 7pm

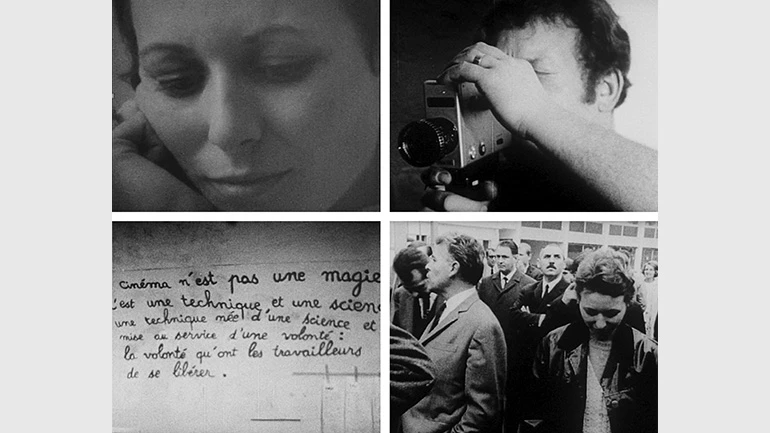

Chris Marker and Mario Marret

À bientôt, j'espère (Be Seing You), 1967

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 43’The Besançon Medvedkin Group

La Charnière (The Hinge), 1968

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 12’

Classe de lutte (The Class of Struggle), 1968

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 40’“Comrades, silence is your worst enemy!” was how film-maker Mario Marret addressed workers on the day he arrived at the Rhodiaceta textile factory in Besançon, the location of a strike that would act as a forerunner to those which came shortly afterwards, in May ’68. The documentary by Marker and Marret portrays the workers’ reflections on their work and day-to-day existence. Without images, La Charnière is an unalloyed soundtrack recording the discussion between the film-makers and workers after the premiere of À bientôt, j’espère, a debate which would give rise to the collective experience of the Medvedkin Groups, who took their name as an homage to Soviet film-maker Aleksandr Medvedkin. Classe de lutte is the first film by the said groups and symbolises a definitive step from a “militant film about workers’ conditions to a militant workers’ film” (Benoliel).

-

Monday, 7 May – 7pm

Session 3

Second session: Thursday, 17 May – 7pm

The Besançon Medvedkin Group

Serie Nouvelle société No. 5 - 7 (New Society Series No. 5–7), 1969–1970

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 30’

Rhodia 4 x 8, 1969

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 4’The Sochaux Medvedkin Group

Sochaux, 11 juin 68 (Sochaux, 11 June ’68), 1970

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 19’Jean-Pierre Thiébaud / The Besançon Medvedkin Group

Le Traîneau-échelle (The Sled-Ladder), 1971

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 8’Michel Desrois / The Besançon Medvedkin Group

Lettre à mon ami Pol Cèbe (A Letter to My Friend Pol Cèbe), 1970

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 17’The alliance between workers and film-makers that cemented in the Medvedkin Groups resulted in an ensemble of films which broke out beyond the conventional parameters of the concept of militant cinema. In generically and ironically alluding to the “new society”, promised at the time by the French Prime Minister, the series Nouvelle Société comprises different conflicts in French factories. In Rhodia 4 x 8, a song by the French militant singer-songwriter Colette Magny accompanies sequences showing the repetitive and gruelling shifts worked on the assembly line. Sochaux, 11 juin 68, meanwhile, recalls one of the most brutal episodes of government repression from May ’68, whereas Le Traîneau-échelle composes a unique visual poem, juxtaposing images of hope with others documenting the horrors of history. One continuous shot-sequence, filmed from the inside of a car, structures Lettre à mon ami Pol Cèbe, whereby the fixed view of the road runs in parallel with the dialogue of three passengers, members of the Medvedkin Groups, who reflect on the potential of militant cinema.

-

Thursday, 10 May – 7pm

Session 4

Second session: Friday, 25 May – 7pm

The Sochaux Medvedkin Group

Les trois-quarts de la vie (Three-Quarters of a Lifetime), 1971

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 18’The Sochaux Medvedkin Group

Week-end à Sochaux (Weekend in Shochaux), 1971

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 53’After 1969, the Sochaux Medvedkin Group would continue with the militant workers’ film project that had germinated in Besançon. In the words of Bruno Muel, the collective worked to “show the cultural prohibitions that must be defeated, that which we could call the usurpation of knowledge, to obtain the means to fight equally against those who think everyone should remain in their place”. Workers from the Peugeot factory in Sochaux, along with advocates of the previous group like Pol Cèbe and Muel, made the films Les trois-quarts de la vie and Week-end à Sochaux to expose the assembly-line working conditions and the engulfing existence of daily work. They refer to “three-quarters of a lifetime”, the title of the first medium-length film, with registers and resources that include an unprecedented, irreverent and satirical theatrical take as close to the popular commedia dell´arte as performance, and explored in greater depth in Week-end à Sochaux.

-

Friday, 11 May – 7pm

Session 5

Second session: Monday, 28 May – 7pm

Bruno Muel / Grupo Medvedkin de Sochaux

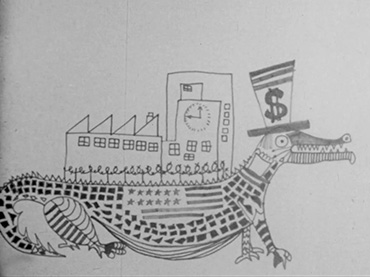

Avec le sang des autres (With the Blood of Others), 1974

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 52’Avec le sang des autres corroborates the break-up of the Medvedkin Groups’ collective experience. Conceived as a common initiative, it was ultimately Bruno Muel who filmed this damning documentary about workplace exploitation at the Peugeot factory in Sochaux, the largest factory in France. The humour and provocative side of the Medvedkin Group’s preceding work is notably lacking here; the assembly line and life’s reduction to a workforce, admin time and time-clock dehumanisation are recorded in an insufferable whole: “In the filming, the workers insisted on both the correct length of the shots — enough to see the progress of the assembly line and to get a feel for the unrelenting noise — and on the importance of filming the workers’ hands,” writes Muel.

-

Monday, 14 May – 7pm

Session 6

Second session: Thursday, 24 May – 7pm

Second session presented by Sylvain George

Jean-Marie Straub

Europa 2005 / 27 octobre (cinétract) (Europe 2005/27 October [Film Tract]), 2006

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 11’

Joachim Gatti, 2009

France, DA, colour, original version with Spanish subtitles, 1’30’’Sylvain George

N'entre pas sans violence dans la nuit (Do Not Go Gentle in the Night), 2005

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 20’.

Ils nous tueront tous (They Will Kill Us All), 2009

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 10’.

Les Nuées (My Black Mama's Face), 2012

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 8’.

Joli mai (celui qui a tué moins de cent fois, qu'il me jette la première pierre) (Beautiful May [let he who has killed fewer than a hundred times cast the first stone]), 2017

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 10’.

Un peu de feu que vole (sa geste en mille éclats) (A Little Fire that Flies [A Gesture in a Thousand Pieces]), 2017

France, DA, b/w, original version with Spanish subtitles, 11 min.The short films by Jean-Marie Straub and Sylvain George demonstrate the continuities and ruptures between the May ’68 cinétracts and the present. The Film-makers’ blatant use of the term is not only a way to designate a set format; it also denotes the affirmation of the historical and political links established with that legacy. Their counter-informative approach stems from the cinétracts made in 1968, in regard to their immediate adherence to contemporary events — the banlieues riots in Paris, political repression, the sans-papiers’ fight for their rights, the refugee camp in Calais and the Nuit debout movement — and their opposition to the dominant language in the media.

![Sylvain George. Un peu de feu que vole (sa geste en mille éclats) (A Little Fire that Flies [A Gesture in a Thousand Pieces]), Film, 2017 Sylvain George. Un peu de feu que vole (sa geste en mille éclats) (A Little Fire that Flies [A Gesture in a Thousand Pieces]), Film, 2017](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/legacy_programs/06_sgeorge-peq.jpg)

Held on 03, 04, 07, 10, 11, 14, 17, 18, 21, 24, 25, 28 May 2018

In May 1968, the defiance of power, mobilised through demonstrations, by reclaiming the streets, new forms of DIY organisation, the occupation of factories and universities and a prolonged general strike was driven primarily by the subversive power from the horizontal gathering of identities and spheres kept apart by society; from collectively speaking out and questioning any form of representation, whether it be political, cultural, or through the media or trade unions.

This collective and anonymous dimension, a pivotal part of the events that transpired, was reflected in cinétracts, cinema “tracts”, or film pamphlets, and the films of the Medvedkin Groups, made by workers and film-makers (producers and technicians) alike. These practices, the fulcrum of this series, built the sturdiest expressions of film-making which contested at once the traditional notion of authorship and the standard devices of film production. These practices appear to reveal that which the philosopher Jacques Rancière has articulated on the very principle of radical democracy and politics: “The recognition of anybody’s power”.

The aforementioned cinétracts are short films with a running time of between two to five minutes, filmed under a policy of anonymity by a number of professional directors, among them Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Chris Marker – responsible for the initiative — and amateur film-makers. Moreover, these works can be seen as the film equivalent to the illustrious May ‘68 posters and graffiti: simple resources and craftsmanship with a fitting visual impact for the purposes of counter-information.

The collective experience of the Medvedkin Groups — named in homage to Soviet film-maker Aleksandr Medvedkin (1900—1989), the creator of the “film-train” in the 1930s — prompted the workers to make militant films. Certain professionals, including Chris Marker, Mario Marret and Bruno Muel, organised workshops in Besançon and Sochaux, and loaned cameras and film-making materials out with the intention of sharing their specialist technical knowledge with the workers, who in turn appropriated the image to create their own representation of the living and working conditions they experienced. This alliance thus gave rise, between 1967 and 1974, to a string of films which exceeded, in content and formal invention, the conventional parameters defining cinéma militant.

In addition to putting forward an approach to the anonymous and collective practices which surfaced around May ‘68, the series sets out to constitute a way of examining the event on the eve of its 50th anniversary. Consequently, along with the cinétracts of ’68, more recent tracts by Straub and Sylvain George will be screened, thus reflecting the ruptures and continuities between that legacy and the present in an insurgent audiovisual genre.

In collaboration with

Curatorship

David Cortés Santamarta

Organised by

Museo Reina Sofía

Más actividades

Institutional Decentralisation

Thursday, 21 May 2026 – 5:30pm

This series is organised by equipoMotor, a group of teenagers, young people and older people who have participated in the Museo Reina Sofía’s previous community education projects, and is structured around four themed blocks that pivot on the monstrous.

This fourth and final session centres on films that take the museum away from its axis and make it gaze from the edges. Pieces that work with that which is normally left out: peripheral territories, unpolished aesthetics, clumsy gestures full of intent. Instead of possessing an institutional lustre, here they are rough, precarious and strange in appearance, legitimate forms of making and showing culture. The idea is to think about what happens when central authority is displaced, when the ugly and the uncomfortable are not hidden, when they are recognised as part of the commons. Film that does not seek to be to one’s liking, but to open space and allow other ways of seeing and inhabiting the museum to enter stage.

![Tracey Rose, The Black Sun Black Star and Moon [La luna estrella negro y negro sol], 2014.](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/styles/small_landscape/public/Obra/AD07091_2.jpg.webp)

On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination

Monday 27, Tuesday 28 and Wednesday 29 of April, 2026 – 16:00 h

The seminar On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination proposes Black Study as a critical and methodological practice that has emerged in and against racial capitalism, colonial modernity and institutional capture. Framed through what the invited researcher and practitioner Ishy Pryce-Parchment terms a Black poethics of contamination, the seminar considers what it might mean to think Blackness (and therefore Black Study) as contagious, diffuse and spreadable matter. To do so, it enacts a constellation of diasporic methodologies and black aesthetic practices that harbor “contamination” -ideas that travel through texts, geographies, bodies and histories- as a method and as a condition.

If Blackness enters Western modernity from the position of the Middle Passage and its afterlives, it also names a condition from which alternative modes of being, knowing and relating are continually forged. From within this errant boundarylessness, Black creative-intellectual practice unfolds as what might be called a history of touches: transmissions, residues and socialities that unsettle the fantasy of pure or self-contained knowledge.

Situated within Black radical aesthetics, Black feminist theory and diasporic poetics, the seminar traces a genealogy of Black Study not as an object of analysis but as methodological propositions that continue to shape contemporary aesthetic and political life. Against mastery as the horizon of study, the group shifts attention from what we know to how we know. It foregrounds creative Black methodological practices—fahima ife’s anindex (via Fred Moten), Katherine McKittrick’s expansive use of the footnote, citation as relational and loving labour, the aesthetics of Black miscellanea, and Christina Sharpe’s practices of annotation—as procedures that disorganise dominant regimes of knowledge. In this sense, Black Study is approached not as a discrete academic field but as a feel for knowing and knowledge: a constellation of insurgent practices—reading, gathering, listening, annotating, refusing, world-making—that operate both within and beyond the university.

The study sessions propose to experiment with form in order to embrace how ‘black people have always used interdisciplinary methodologies to explain, explore, and story the world.’ Through engagements with thinkers and practitioners such as Katherine McKittrick, C.L.R. James, Sylvia Wynter, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, Hilton Als, John Akomfrah, fahima ife and Dionne Brand, we ask: What might it mean to study together, incompletely and without recourse to individuation? How might aesthetic practice function as a poethical intervention in the ongoing work of what Sylvia Wynter calls the practice of doing humanness?

Intergenerationality

Thursday, 9 April 2026 – 5:30pm

This series is organised by equipoMotor, a group of teenagers, young people and older people who have participated in the Museo Reina Sofía’s previous community education projects, and is structured around four themed blocks that pivot on the monstrous.

The third session gazes at film as a place from which to dismantle the idea of one sole history and one sole time. From a decolonial and queer perspective, it explores films which break the straight line of past-present-future, which mix memories, slow progress and leave space for rhythms which customarily make no room for official accounts. Here the images open cracks through which bodies, voices and affects appear, disrupting archive and questioning who narrates, and from where and for whom. The proposal is at once simple and ambitious: use film to imagine other modes of remembering, belonging and projecting futures we have not yet been able to live.

Remedios Zafra

Thursday March 19, 2026 - 19:00 h

The José Luis Brea Chair, dedicated to reflecting on the image and the epistemology of visuality in contemporary culture, opens its program with an inaugural lecture by essayist and thinker Remedios Zafra.

“That the contemporary antifeminist upsurge is constructed as an anti-intellectual drive is no coincidence; the two feed into one another. To advance a reactionary discourse that defends inequality, it is necessary to challenge gender studies and gender-equality policies, but also to devalue the very foundations of knowledge in which these have been most intensely developed over recent decades—while also undermining their institutional support: universities, art and research centers, and academic culture.

Feminism has been deeply linked to the affirmation of the most committed humanist thought. Periods of enlightenment and moments of transition toward more just social forms—sustained by education—have been when feminist demands have emerged most strongly. Awareness and achievements in equality increase when education plays a leading social role; thus, devaluing intellectual work also contributes to harming feminism, and vice versa, insofar as the bond between knowledge and feminism is not only conceptual and historical, but also intimate and political.

Today, antifeminism is used globally as the symbolic adhesive of far-right movements, in parallel with the devaluation of forms of knowledge emerging from the university and from science—mistreated by hoaxes and disinformation on social networks and through the spectacularization of life mediated by screens. These are consequences bound up with the primacy of a scopic value that for some time has been denigrating thought and positioning what is most seen as what is most valuable within the normalized mediation of technology. This inertia coexists with techno-libertarian proclamations that reactivate a patriarchy that uses the resentment of many men as a seductive and cohesive force to preserve and inflame privileges in the new world as techno-scenario.

This lecture will address this epochal context, delving into the synchronicity of these upsurges through an additional parallel between forms of patriarchal domination and techno-labor domination. A parallel in which feminism and intellectual work are both being harmed, while also sending signals that in both lie emancipatory responses to today’s reactionary turns and the neutralization of critique. This consonance would also speak to how the perverse patriarchal basis that turns women into sustainers of their own subordination finds its equivalent in the encouraged self-exploitation of cultural workers; in the legitimation of affective capital and symbolic capital as sufficient forms of payment; in the blurring of boundaries between life and work and in domestic isolation; or in the pressure to please and comply as an extended patriarchal form—today linked to the feigned enthusiasm of precarious workers, but also to technological adulation. In response to possible resistance and intellectual action, patriarchy has associated feminists with a future foretold as unhappy for them, equating “thought and consciousness” with unhappiness—where these have in fact been (and continue to be) levers of autonomy and emancipation.”

— Remedios Zafra

27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference

Wednesday, 4, and Thursday, 5 March 2026

The 27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference, organised by the Museo Reina Sofía’s Department of Conservation and Restoration, with the sponsorship of the Mapfre Foundation, is held on 4 and 5 March 2026. This international encounter sets out to share and debate experience and research, open new channels of study and reflect on conservation and the professional practice of restorers.

This edition will be held with in-person and online attendance formats, occurring simultaneously, via twenty-minute interventions followed by a five-minute Q&A.