Held on 26 Apr 2022

Free Unions is a series of events, tours and activations that take place in the rooms of Communicating Vessels. Collection 1881–2021, the new rehang of the Museo Reina Sofía Collection. The programme is made up of different thematic strands, the title alluding to the poem Free Union (1931) by André Breton in its definition of psychic automatism as an alternative to rationalism. The transgressive spirit of that poem, which takes apart rational discourse through a lexical juxtaposition to generate other relationships and significations, governs this public programme, in which recitals, readings, debates, performances and actions in these rooms transgress the aura of the white cube.

The first of these events, Avant-garde Gatherings, is activated in rooms 201.01, 201.02 and 201.03. Holy Bohemia. Madrid, Paris, Barcelona and Room 202.03. Stridentopolis. An Urban Utopia, in which a fin de siècle cuplé and a series of machine-like, phonetic sound concerts on these early avant-garde movements are performed. This drift seeks to retrieve the sounds, attitudes and different forms of experiencing the city that shared time and space with this early bohemia via cuplés. The cuplé was conceived as a music genre with a double form: at once iconoclastic, transgressive and sexual and with empowered and feminist lyrics, as well as a mise en scène linked to the absurdism and nonsensicality of Dadaism and its cabaret scenes.

The second part of the programme approaches music and sound poetry in outlying historical avant-garde movements, such as Vibrationism and Ultraism in Spain and Stridentism in Mexico, movements which reflect on sound and modernity and hold a prominent place in the new arrangement of the Museo’s Collection.

This programme resituates such movements from the music and poetry they generated, in parallel to the visual arts, now exhibited in the Museo’s rooms to initiate other dialogues.

Tuesday, 26 April 2022 – 7pm

First part. A Sicaliptic, Ultraist Bohemian Drift

[dropdown]

In homage to all those stars from a forgotten constellation who sang about daily life and urban advances during the long Silver Age.

“The modest and timid writers saw in that woman (La Chelito) a comrade in the struggles against a dark present. They would all break down the walls of boredom [...]”.

Ramón Gómez de la Serna, “The Globe and Discovery of La Chelito”, 1930

This drift retrieves the sounds, attitudes and different forms of city living that shared time and space with the bohemia of the Silver Age. Víctor Fuentes ensured that there were three native promotions of bohemians. The rehang of the Museo Reina Sofía Collection is traversed by the second, Holy Bohemia in Madrid, Paris and Barcelona, and the third, where poets from El movimiento V. P. emerged with incendiary words, mocking grins, nihilistic intentions, rebellious gestures and futurist brains. Thus, they journey through the exhibition rooms singing the cuplés that show the other side of the same reality with malice, cunning and implausible equilibrium, the worst ulterior motive and joking around: the predictable ending to the film La revoltosa (The Troublemaker, Florián Rey, 1924) contrasts with the lyrics of Guasa viva (Living Humour), a satire on marriage; those women who “lived the wrong life” — an allusion to the book by Constancio Bernaldo de Quirós from 1901 — demand their place in the pantheon of Madrid’s underworld, the coils of smoke from their cigarettes recalling a time of sensual pleasure and the right to sexual enjoyment; Paris arrives with its light and inspiration; Félix Limendoux, a holy bohemian, invents the term that gives meaning to a large part of the musical production from the time: “the sicalipsis”.

By way of cuplés and concerts that are part of the first programme, these gallant, frivolous and chic women, half epileptic, half syphilitic, gift Picasso a “frivolous queen” and Hermen Anglada Camarasa a Cocaine Tango. Exalted voluptuousness, impotent energies and intoxicated flowers lead to a renewed bohemia, where old young poets and young old poets write a manifesto, publish a magazine and try, unsuccessfully, to provoke a scandal. The voltaic eyes and telescopic legs of new female beauty announce the true “pure ultraism”, and the wonderful poetic dresses of Sonia Delaunay (Sofinka Modernuska) allow poems to be performed now and always.

[/dropdown]

Felipe Orejón. Guasa viva (Living Humour)

A creation by Laura Inclán, La Verbeníssima, 2022, based on the premiere by Carmen Flores, 1920

Félix Garzo (lyrics) and Joan Viladomat (music). Fumando espero (Smoking, I Wait)

A creation by Aldegunda Vergara, the cuplé Goddess, 2022, based on the premiere by Pilar Arcos, 1922

Remar y Eddy (lyrics) and Laura Inclán (music). La reina frívola (The Frivolous Queen)

A creation by Laura Inclán, La Verbeníssima, 2022, based on the premiere by Consuelo Hidalgo, 1923. Version set to music by La Verbeníssima in the absence of the original score.

Amichatis (lyrics) and Juan Viladomat (music). Tango de la cocaína (Cocaine Tango)

A creation by Aldegunda Vergara, the cuplé Goddess, 2022, based on the premiere by Ramoncita Rovira, 1926

Joaquín Marino (lyrics) and M. Font de Anta (music). ¡¡Ultraísmo puro!! (Pure Ultraism!!)

A creation by Laura Inclán, La Verbeníssima, 2022, based on the premiere by Amalia de Isaura, 1922

Credits

Performers

Gallant and sicaliptic cuplé singers: Laura Inclán, La Verbeníssima, and Aldegunda Vegara, the cuplé Goddess

Piano: Patricia Pérez

Poetic garment: Drina Marco

Programme: Gloria G. Durán (University of Salamanca)

Segunda parte. Concierto vibracionista y estridentista

[dropdown]

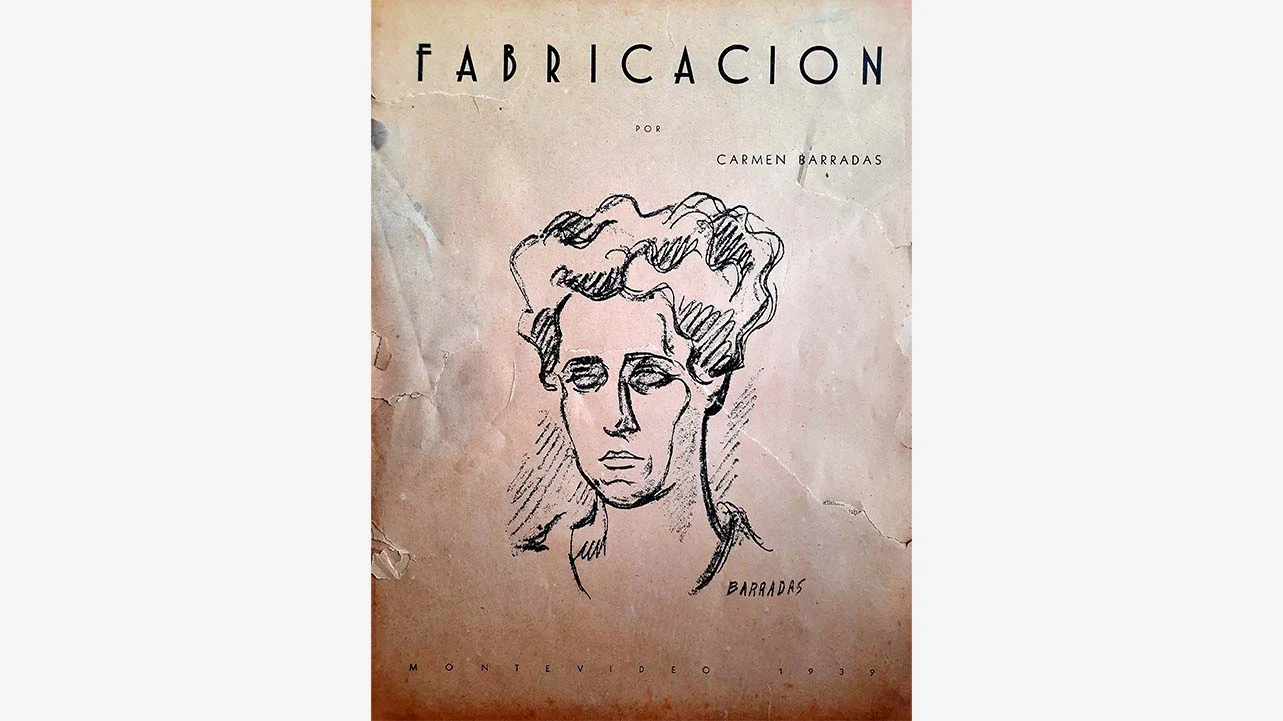

In homage to the vibrationist-ultraist composer Carmen Barradas (1888–1963) and the centenary of her piano recital in the Ateneo de Madrid (1922–2022)

“This is my sister, a spiritual figure and an evasive Russian student, English feminist and Polish or Austrian Pianist”.

Rafael Barradas

This concert spotlights the music and sound poetry of outlying historical avant-garde movements, such as Vibrationism and Ultraism in Spain and Stridentism in Mexico, which reflect on sound and modernity and play a prominent role in the rearrangement of the Collection. From Vibrationism and Ultraism, the music of composer Carmen Barradas is performed, an artist who spent a long period in the shadow of her brother, the painter Rafael Barradas, and whose contribution to Spanish avant-garde art is only just being appreciated now. In 1920, the co-founder of Ultraism, Guillermo de Torre, pointed to her as a unique representative of the “musical ramification” of the movement. Consequently, the concert means to grant recognition and pay homage to the piano recital she performed in the Ateneo de Madrid in 1922. The music is accompanied by the recital of phonetic Ultraist poems released in the same era.

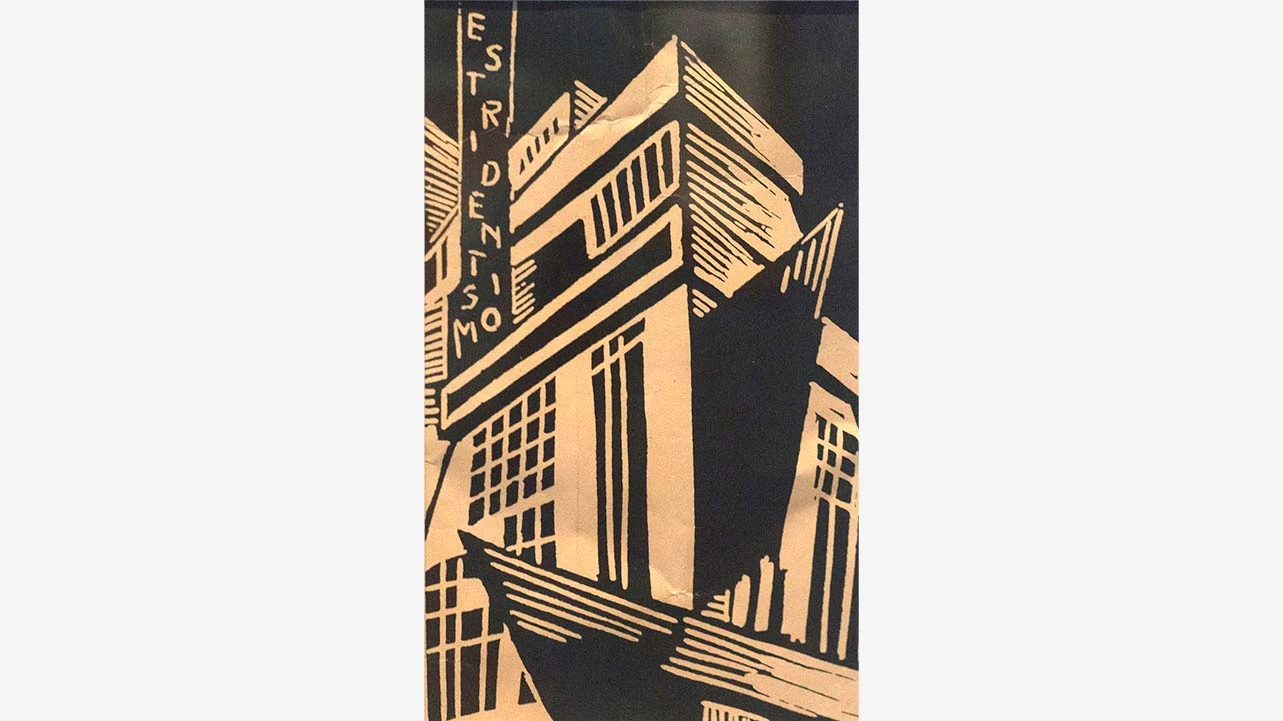

Ultraism also influenced other Latin American avant-garde movements, for instance Mexican Stridentism (1921–1927), the uniqueness of which was based on carrying out a political projection in social and cultural practice. This was made possible by the participation of Stridentists inside Heriberto Jara’s government in the State of Veracruz (1924–1927), rebaptising, among other initiations, the capital, Xalapa, as Stridentopolis. The concert is performed in the room sharing the same name — Room 202.03. Stridentopolis. An Urban Utopia, relating the texts from magazines and books displayed to the visual works exhibited. As an epilogue to the movement and concert, a total artwork joins a mask-megaphone sculpture by Stridentist Germán Cueto, the verbal music of Michel Seuphor and the noise sounds of Futurist Luigi Russolo, carried out inside the framework of the exhibition Cercle et Carré (1930) in Galerie 23 in Paris.

Vibrationism (1917–1920) y ultraism (1918–1926)

Carmen Barradas. Cajita de music (Little Music Box)

Piano, ca. 1915

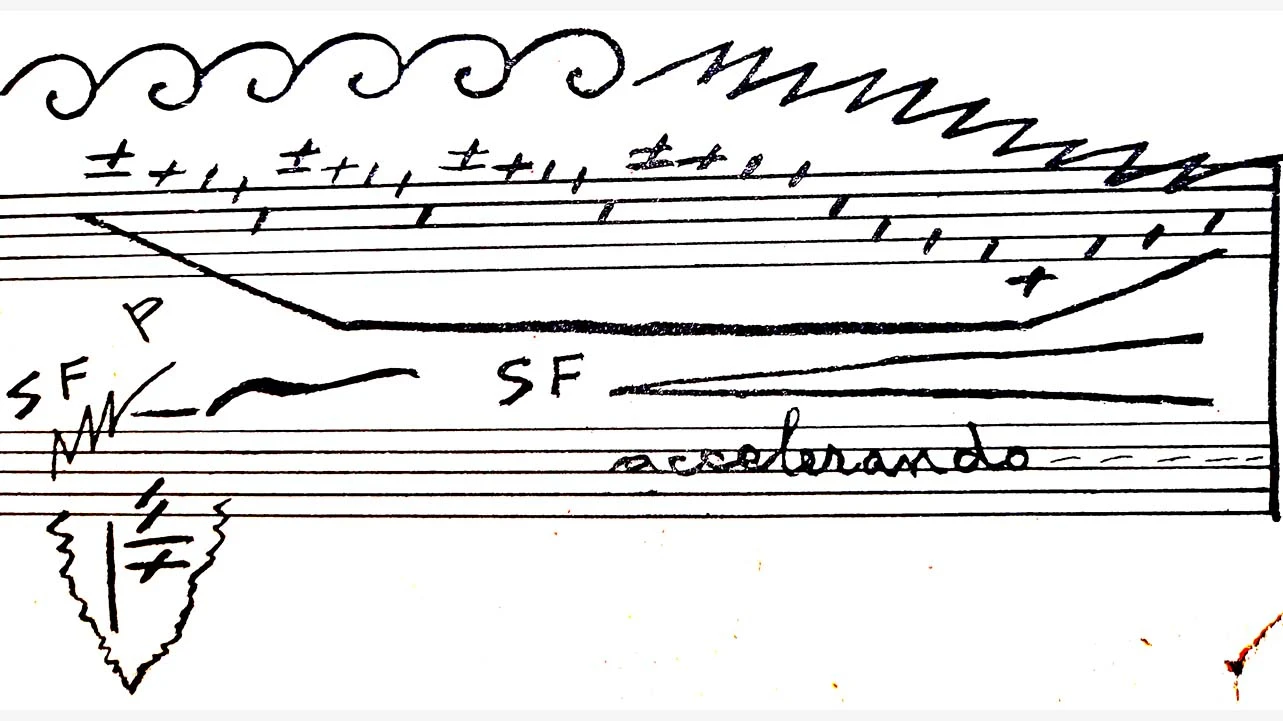

Carmen Barradas. Fabricación (Manufacturing)

Piano and MIDI version for factory noise, 1922

Rafael Barradas. Bonanitingui

Vibrationist drawing, 1917

Xabier Bóveda. El tranvía (The Tram)

Phonetic poem, 1919

Carmen Barradas. Espera el coche (Waiting for the Car)

Piano and bell, 1923

Carmen Barradas. Poema de una calle (Nocturno) [Poem of a Street] (Night-time)

Piano, 1919

Lucía Sánchez Saornil. Panoramas urbanos (espectáculo) (Urban Landscapes) (Spectacle)

Poem, 1921

Francisco Vighi. Celestiales fuegos artificiales (Celestial Fireworks)

Poem, 1920

Carmen Barradas. Piratas (Pirates)

Piano, 1923. Unfinished manuscript, based on a text by Ultraist José de Ciria y Escalante

Carmen Barradas. Taller mecánico (Mechanical Workshop)

Piano, 1928. Unfinished manuscript

Jacobo Sureda. Concinación (Harmonious)

Phonetic poem, 1926

Fernando María Milicua. A caballo, río y Martín Pescador (Horseback, River and Kingfisher)

Phonetic poem, 1925

Rafael Cansinos Assens. Dada medical (Medical Dada)

Unpublished from Jacques Doucet’s Literary Library. Homage to the failed Ultra-Dada festival, 1921

stridentism (1921–1927)

Manuel Maples Arce. Irradiador estridencial (Stridentist Irradiator)

Calligram, 1923

José Pomar. Piano percusivo para Preludio y fuga rítmicos (Percussive Piano for Rhythmic Prelude and Fugue)

Piano extract with drumstick and piece of wood, 1932

Kyn Taniya. Números (Numbers)

Radiophonic poem, 1924

Xavier Icaza. Panchito Chapopote

Book extract, 1926

Stridentist-Futurist-Geometric Abstraction Epilogue

Germán Cueto with Michel Seuphor and Luigi Russolo. Máscara-megáfono (Mask-Megaphone)

Verbal and noise music, 1930

Credits

Performers

Piano: Patricia Pérez

Voice: Jesús Ge

MIDI: Leopoldo Amigo and Miguel Molina

Mask-megaphone: Paco Benavent

Radio-head: Rosa Mira

Programme: Miguel Molina Alarcón (Universitat Politècnica de València) and José Luis Espejo

[/dropdown]

Organised by

Museo Reina Sofía

Programme

Free Unions

Inside the framework of

Más actividades

![Tracey Rose, The Black Sun Black Star and Moon [La luna estrella negro y negro sol], 2014.](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/styles/small_landscape/public/Obra/AD07091_2.jpg.webp)

On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination

Monday 27, Tuesday 28 and Wednesday 29 of April, 2026 – 16:00 h

The seminar On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination proposes Black Study as a critical and methodological practice that has emerged in and against racial capitalism, colonial modernity and institutional capture. Framed through what the invited researcher and practitioner Ishy Pryce-Parchment terms a Black poethics of contamination, the seminar considers what it might mean to think Blackness (and therefore Black Study) as contagious, diffuse and spreadable matter. To do so, it enacts a constellation of diasporic methodologies and black aesthetic practices that harbor “contamination” -ideas that travel through texts, geographies, bodies and histories- as a method and as a condition.

If Blackness enters Western modernity from the position of the Middle Passage and its afterlives, it also names a condition from which alternative modes of being, knowing and relating are continually forged. From within this errant boundarylessness, Black creative-intellectual practice unfolds as what might be called a history of touches: transmissions, residues and socialities that unsettle the fantasy of pure or self-contained knowledge.

Situated within Black radical aesthetics, Black feminist theory and diasporic poetics, the seminar traces a genealogy of Black Study not as an object of analysis but as methodological propositions that continue to shape contemporary aesthetic and political life. Against mastery as the horizon of study, the group shifts attention from what we know to how we know. It foregrounds creative Black methodological practices—fahima ife’s anindex (via Fred Moten), Katherine McKittrick’s expansive use of the footnote, citation as relational and loving labour, the aesthetics of Black miscellanea, and Christina Sharpe’s practices of annotation—as procedures that disorganise dominant regimes of knowledge. In this sense, Black Study is approached not as a discrete academic field but as a feel for knowing and knowledge: a constellation of insurgent practices—reading, gathering, listening, annotating, refusing, world-making—that operate both within and beyond the university.

The study sessions propose to experiment with form in order to embrace how ‘black people have always used interdisciplinary methodologies to explain, explore, and story the world.’ Through engagements with thinkers and practitioners such as Katherine McKittrick, C.L.R. James, Sylvia Wynter, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, Hilton Als, John Akomfrah, fahima ife and Dionne Brand, we ask: What might it mean to study together, incompletely and without recourse to individuation? How might aesthetic practice function as a poethical intervention in the ongoing work of what Sylvia Wynter calls the practice of doing humanness?

Intergenerationality

Thursday, 9 April 2026 – 5:30pm

This series is organised by equipoMotor, a group of teenagers, young people and older people who have participated in the Museo Reina Sofía’s previous community education projects, and is structured around four themed blocks that pivot on the monstrous.

The third session gazes at film as a place from which to dismantle the idea of one sole history and one sole time. From a decolonial and queer perspective, it explores films which break the straight line of past-present-future, which mix memories, slow progress and leave space for rhythms which customarily make no room for official accounts. Here the images open cracks through which bodies, voices and affects appear, disrupting archive and questioning who narrates, and from where and for whom. The proposal is at once simple and ambitious: use film to imagine other modes of remembering, belonging and projecting futures we have not yet been able to live.

Remedios Zafra

Thursday March 19, 2026 - 19:00 h

The José Luis Brea Chair, dedicated to reflecting on the image and the epistemology of visuality in contemporary culture, opens its program with an inaugural lecture by essayist and thinker Remedios Zafra.

“That the contemporary antifeminist upsurge is constructed as an anti-intellectual drive is no coincidence; the two feed into one another. To advance a reactionary discourse that defends inequality, it is necessary to challenge gender studies and gender-equality policies, but also to devalue the very foundations of knowledge in which these have been most intensely developed over recent decades—while also undermining their institutional support: universities, art and research centers, and academic culture.

Feminism has been deeply linked to the affirmation of the most committed humanist thought. Periods of enlightenment and moments of transition toward more just social forms—sustained by education—have been when feminist demands have emerged most strongly. Awareness and achievements in equality increase when education plays a leading social role; thus, devaluing intellectual work also contributes to harming feminism, and vice versa, insofar as the bond between knowledge and feminism is not only conceptual and historical, but also intimate and political.

Today, antifeminism is used globally as the symbolic adhesive of far-right movements, in parallel with the devaluation of forms of knowledge emerging from the university and from science—mistreated by hoaxes and disinformation on social networks and through the spectacularization of life mediated by screens. These are consequences bound up with the primacy of a scopic value that for some time has been denigrating thought and positioning what is most seen as what is most valuable within the normalized mediation of technology. This inertia coexists with techno-libertarian proclamations that reactivate a patriarchy that uses the resentment of many men as a seductive and cohesive force to preserve and inflame privileges in the new world as techno-scenario.

This lecture will address this epochal context, delving into the synchronicity of these upsurges through an additional parallel between forms of patriarchal domination and techno-labor domination. A parallel in which feminism and intellectual work are both being harmed, while also sending signals that in both lie emancipatory responses to today’s reactionary turns and the neutralization of critique. This consonance would also speak to how the perverse patriarchal basis that turns women into sustainers of their own subordination finds its equivalent in the encouraged self-exploitation of cultural workers; in the legitimation of affective capital and symbolic capital as sufficient forms of payment; in the blurring of boundaries between life and work and in domestic isolation; or in the pressure to please and comply as an extended patriarchal form—today linked to the feigned enthusiasm of precarious workers, but also to technological adulation. In response to possible resistance and intellectual action, patriarchy has associated feminists with a future foretold as unhappy for them, equating “thought and consciousness” with unhappiness—where these have in fact been (and continue to be) levers of autonomy and emancipation.”

— Remedios Zafra

ARCO2045. The Future, for Now

Saturday 7, March 2026 - 9:30pm

The future, its unstable and subjective nature, and its possible scenarios are the conceptual focus of ARCOmadrid 2026. A vision of the future linked to recent memory, a flash of insight into a double-edged sword. This year's edition, as in the previous two, will once again hold its closing party at the Reina Sofia Museum. This time, the star of the show is Carles Congost (Olot, Girona, 1970), one of the artists featured in the new presentation of the Collections recently inaugurated on the 4th floor of the Sabatini Building.

Carles Congost, with his ironic and timeless gaze, is responsible for setting the tone for this imperfect future, with a DJ session accompanied by some of his works in the Cloister on the first floor of the Sabatini Building of the Museo on the night of Saturday 7 March.

27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference

Wednesday, 4, and Thursday, 5 March 2026

The 27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference, organised by the Museo Reina Sofía’s Department of Conservation and Restoration, with the sponsorship of the Mapfre Foundation, is held on 4 and 5 March 2026. This international encounter sets out to share and debate experience and research, open new channels of study and reflect on conservation and the professional practice of restorers.

This edition will be held with in-person and online attendance formats, occurring simultaneously, via twenty-minute interventions followed by a five-minute Q&A.