Critical Practices Seminar

Reversible Modernities

This conversation forms part of one of three seminars on critical practices held in 2010-11 under the aegis of the Museum’s Master’s program in History of Art.

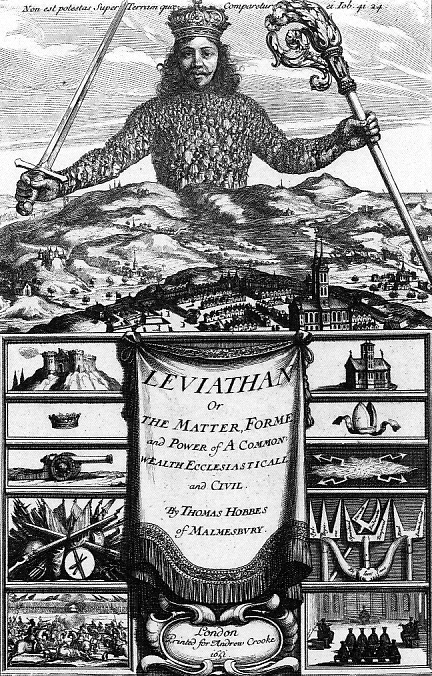

Here, Albert Corsín, research anthropologist at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the leading professor in the seminar, and his guest, Rane Willerslev, ethnologist and anthropologist at Aarhus University in Denmark, suggest that three principles liken the Baroque, its philosophical forms and anthropological knowledge to contemporary social and critical theory: the analysis of the mass media, the analysis of emotions and the analysis of machines.

This is why a soundtrack is playing in the background of the conversation with recordings of machines, clocks and music boxes – musical machines – from the 17th century, the beginnings of a technological aurality. This dialogue discusses the particular features and reflections of Baroque thinking discernible today from the point of view of anthropology, which involves looking at animism, one of the first forms of religion and spirituality on which Satanism, among other things, is based.

This presentation of an anthropology of emotions illustrates how scientistic, rationalist analysis omits essential political and social nexuses. The seminar uses this idea to demonstrate the fallibility of central modernity and empiricism, developing its opposite – a modernity linked to other forms of thinking like animism, and thus steering clear of narratives that are fixed and stagnant.

José Luis Espejo

Luis Mata