Hello, my name is Robin Rimbaud, although some people simply know me as Scanner. I am a composer and sound artist. I've been working with sound since I was about 11 years old, when I was recording everything from the sound of our holidays on cassette, rather than with a camera, and still have every tape I've ever recorded. So, I can even listen back to my brother and myself fighting over biscuits when I was just 13 years old. Yes, seriously. In some ways, I've been a documentist. As with all the tapes, I've also kept a diary every day since I was 12 years old and never missed a day. My practice is extremely varied. I've worked with film directors, architects, fashion designers, visual artists and so on. And, well, like many of my peers, it's hard to pin me down to just one thing. I've released so many albums, I actually have no idea how many are out there in the world either.

I first discovered the work of German composer Roland Kayn purely by chance. I was staying at a tiny house of my Dutch friend Roland Spekler, who was a music producer in Utrecht, in the Netherlands. I was sleeping in his little guest bedroom and the shelves were filled with all manner of intriguing records, publications and objects. In fact, at one end of the room there was even a huge gong that the American composer Charlemagne Palestine had stored there, I think. Anyhow, Roland had a stack of these box sets on the shelf, featuring the work of Roland Kayn. I had no chance to listen to the work then as there was no record deck in the room, but once back home, I began to explore his work, well, at least I tried to.

Remember, this was in the late 1990s, so much more of a challenge than it would be today. In fact, for many years I even thought Kayn was Dutch- born, but later discovered that he moved there in 1970 from Germany. Some listeners might be aware there's been an amazing effort made by Kayn's daughter, Ilse, over recent years to ensure his vast body of work is made available. So, every month, almost without fail, a new release emerges online. And there's a nice little story related to this too. At one point Ilse wrote to me, knowing I was on my way over to the Netherlands, and invited me to go ice skating together. Given that the last time I went ice skating I couldn't use my right hand for about six months as I slipped and someone skated over my hand on the ice, I politely declined. That's not to say it won't happen though.

I love the mystery of Kayn’s work more than anything else. Though radically different, sometimes it brings to mind the work of German filmmaker Michael Haneke, whose films remain with you long after you've seen them. As with Kayn, you are often left looking for answers, when nothing is explicit. And you, as the viewer, or with Kayn as the listener, you need to make the effort if you want to unravel what you've experienced, and for me that's one of the highlights, the kind of unknowing in a sense. There are no easy entry points. The works begin, they continue, and they end. This actually sounds almost like the description of a Samuel Beckett novel or play, but actually it's true. It's almost as if Kayn refuses to follow any guidelines or unwritten rules that have been established with experimental music.

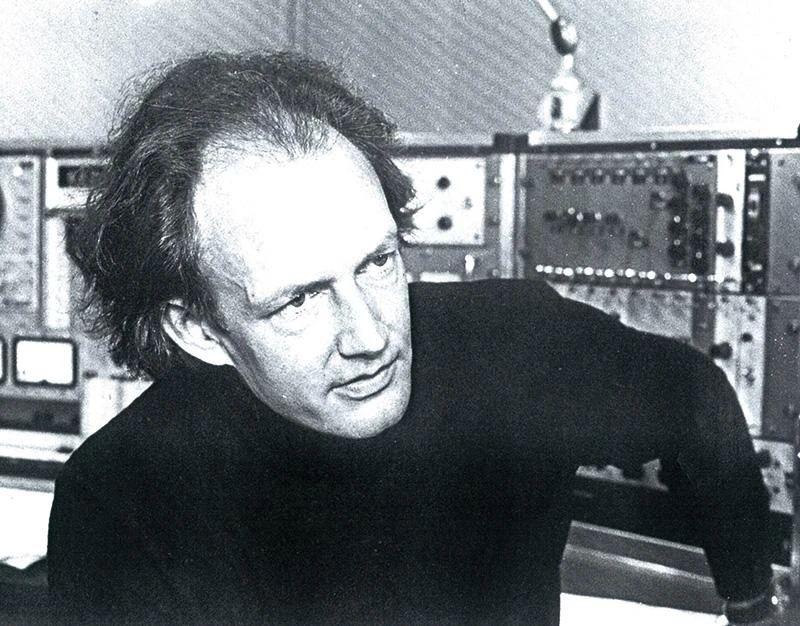

For me, one of the most appealing aspects to Kayn's work is how on earth did he make it? For much of the time it's almost impossible to recognize the source material. Is it sampled from somewhere? Are they environmental recordings that have been processed, filtered and treated? What are the origins of this mysterious sound? In this sense, Kayn is rather unique in the position he occupies within the field of experimental music. It's known that he worked in Utrecht's Institute of Sonology, which is still active today, though currently based in Den Haag. I find it fascinating to consider how Kayn was working and creating at the same time as Stockhausen, Feldman, Xenakis and others, but sounds just so radically different.

I suppose in many ways it's not surprising that he's not better known, since he remained relatively obscure during his lifetime, which wasn't helped at all since his music was rarely performed live either. The irony is, of course, that his body of work now largely outweighs many of his contemporaries, at least in terms of the number of recordings. Indeed, I just checked, and at present I have almost five days' worth of Kayn material in my collection, and that's five days without sleep, eating or going to the toilet. Then again, perhaps you can never have too much of a good thing, as they say. For work that is unfamiliar to a listener, it's often of value to consider more contemporary work that resonates, perhaps just to offer a context or a place for it today.

There are a number of artists who come to mind for me when listening back to the work of Kayn today. I especially hear this within the field of ambient and industrial music. One artist that comes to mind is that of the The Hafler Trio, which is essentially now the work of just one person, Andrew McKenzie. Rather enigmatic, The Hafler Trio offers up a unique combination of electronics mixed with environmental recordings and noise. Like Kayn, the work of The Hafler Trio often extends over long periods, often exceeding an hour in length. And again, like Kayn, what seems perhaps to be on the surface to be rather simple is in fact ever moving and changing. They both seem to celebrate the rich harmonic qualities of singular, fundamental sounds, and exploit these over long durations. They can be ugly and sublime at the very same time, yet equally exhilarating. There’s a dreamlike quality to both of their works. It's curious to consider this sonic relationship too, especially since they both come from very different traditions indeed.

Another artist who comes to mind is American musician Jim O' Rourke, who has taken a key role in the recent reissues of Kayn's work and mastered the early recordings for release. His Steamroom releases, as he calls them, which began in 2013, now number over 60 albums at this point in 2024. These works explore a variety of textual and abstract moods, often focusing on field recordings, sustained mutating notes, surge synthesizer explorations and much more. Sometimes they feel as if you're almost listening to private sonic diaries at times. And, like Kayn, it's almost impossible to discern an obvious structure. Indeed, it often feels more about the sense of drift than anything else. These are self- sustaining works and, like Kayn, feel like music that is made at heart for the creator themselves, with less focus or even concern about an audience.

Another interesting reference point is the American sculptor and designer Harry Bertoia and his Sonambient recordings. Bertoia created sound sculptures in all shapes and sizes using copper and bronze rods. When tapped, these rods would then sway and collide, creating resonant frequencies. They produced this microtonal wall of eerie, cavernous harmonic soundscapes. Listening to a work from Kayn, like Yellowings Conglomerations Part II, immediately brings to mind these works of Bertoia. They are radiant, complex soundscapes and utterly beautiful. I remember many years ago often seeing the small edition press-ins that Bertoia made sitting in boxes in record shops and design stores, especially in America, and usually at bargain prices. And, yes, of course, I now wonder why I didn't bother to pick them up at the time too.

I often wonder if I, like others, are drawn to works that bear some resemblance to your own work or ideas. When I listen to Kayn, I'm sometimes reminded of very early tape works I made in the 1980s, completely unaware of this kind of music at the time. There was no YouTube or Spotify to offer a fast- track entrance to such music, and even if you read about it sometimes, you simply just had to imagine it. So, back to my teenage days for a moment. I would make enormous tape loops with an old reel-to-reel tape deck that my English teacher at school had given me, and I ran the tape around a milk bottle on the other side of the room. So, by recording a single sound on my guitar, it would then return to me 30 seconds or a minute later, depending on just how long the tape was. But more interestingly, I would hang a cheap microphone out of the window and leave it running, live, so anything that occurred outside our house would also combine with the guitar sounds, for example. So, someone walking past, or somebody cycling on would immediately become part of this overall abstract daily tapestry. I can hear this kind of effect when I listen to the section Torego 3 from Tektra. It makes me think of sitting in an enormous public square, and the sounds of the world around you, traffic, voices, the general ambience of a city, are filtered through the buildings, transformed into this glacial blur, unable to pick one singular sound source. Or the sound inside an airport, where the architecture itself seems to devour the edges of any sound, dispelling them into one sensational, mysterious, sonic ambience. And, sometimes, it sounds rather like Wagner or Mahler played in a forest and a mountain several miles away, blurred and out of focus.

In preparing for this broadcast, naturally, I made some research and found some revealing information regarding source materials of some of Kayn's work. Apparently, his piece Cybernetics I features sounds that are actually all of vocal origin, including animal noises, which were then fed through tape into a series of audio processing machines, such as reverb, filter and ring modulators, and they were then mixed into 10 separate sound sources, which were again mixed in real time and recorded to tape again. This kind of process brings to mind for me Alvin Lucier's revolutionary work, I Am Sitting in a Room, where the voice of the composer was recorded, and then played back into the space and recorded again within the room and then recorded again and again and again. So, what you finally hear as a listener is the gentle disappearance of his voice, and instead the natural acoustic phenomena of the room itself reveals itself. The words evaporate, becoming distant, and very soon the text becomes an abstract sonic landscape. Listening to Kayn's work, it's quite possible that much of the source material was indeed from the natural world and left to processes like this. The textures of Kayn's work offer a sense of stasis at some points, but again, how were these smeary, disorienting sounds actually made?

Kayn had a deep interest in synthesizers and especially their ability to conjure up these glacial worlds of sound like never before. He often referred to his work as cybernetic music, where he was using a system, a network of feedback and control, which meant that he could almost set the works in motion, and they began to take on a life of their own. It was impossible to anticipate how a particular work might turn out at times using such a process. Interestingly, Kayn himself acknowledged that his works even questioned the very concept of authorship at times. It was Kayn's interaction with the philosopher Max Bense, a professor at the Technical University in Stuttgart, Germany, that inspired him towards this direction.

Bense was one of the earliest thinkers to adopt these cybernetic concepts to art and aesthetics, since they were already familiar in maths, physics, biology and so on. And it was Kayn's time at the Institute of Sonology that truly allowed him to explore these concepts. Even in the 1960s, the studio there was kitted out with all kinds of modular synthesizers and computers, so that Kayn could essentially program the unprogrammable. And in that way, he could set these generative feedback systems into motion and see what emerged. Indeed, Kayn's embracing of such self- sustaining musical systems, which could produce infinite soundscapes of vastly differing textures and moods, led to a massive output of work. I could explain why there's such a regular amount of material emerging from his archives. Given how at the time he was releasing three and four LP box sets of his work, attests to the sheer volume of material he was able to output from this system. And in fact, it's that very aspect that first appealed to me about modular synthesis.

I've long been an admirer of the work of American musician and composer, David Tudor, and his work with electronics and developing generative systems. And so, these kinds of modular systems, where you can pick and choose different modules to create different effects, different sounds, and so on, was really appealing to me. Tudor's inclusive yet exploratory approach to the use of electronics in performance and composition presented listeners with an abstract, expressionistic ocean of sound, risky and inventive, not unlike Kayn. You could find and develop your own voice in this way. There's an openness to it, and there's a sense of discovery and surprise, which is something that's never left me using these systems. It offered a way to create work outside of a pattern I'd become accustomed to over the and has continued to propel me in fresh directions. So, in some ways, this cybernetic approach has played a role in my own life too, even if I've never really used the term myself.

Back in 1968, there was a daylong event the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London entitled Cybernetic Serendipity, which explored the patterns and impact of emerging technologies. I was unfortunately still at primary school at the time, so more occupied with playing with my toys and soldiers and so on. But over the years, I've discovered more and more about this event. Peter Zinovieff of EMS Synthesizers set up his studio equipment there and devices for generating music were made available to the public. Artists such as Nam June Paik, Gustav Metzger, and Jean Tinguely and others displayed their work too. And there was also this amazing 10 track LP that was released to accompany the show, which is a wonderful collection of works featuring such artists as John Cage, Xenakis, Herbert Brün, and others. I'm certain that Kayn must have been familiar with this exhibition, as he later released a work with the identical title, Cybernetic Serendipity, in 1987. And in a way, this leads us to another great connection, British musician Brian Eno.

Eno had been exposed to cybernetics as a teenager at college. Via his tutor, artist Roy Ascot, students were opened up to radical new ways of thinking. Indeed, Ascot has remained a leading figure in computer art, electronic art, and cybernetic art over the years. I find it fascinating that Kayn and Eno might both have been influenced by the ideas of cybernetics, but the net results were increasingly different. It's worth noting as well that Eno's late friend, the artist Peter Schmidt, played a huge role in the story of cybernetics too. Schmidt contributed artwork to many of Eno's key albums in the 1970s, and helped develop the Oblique Strategies, which is a set of playing cards that assist with creative problems whilst working in the studio. And Schmidt was also a music advisor for the ICA exhibition back in 1968, so the connections really make sense. Though perhaps using similar thought and creative principles, Kayn and Eno occupy very different places, though, in the music world. Eno has always come far more from a pop ideology and used generative systems to create music deeply ingrained in traditional harmonic relationships. These self-determining systems, as such certainly offered Eno a way to produce popular music as an acknowledged non-musician, as he's always called himself.

You're now listening to a passage from The Art of Sound. But again, just listening to it proves impossible to date. Any reference points are blurred and erased. It feels unanchored, as if about to float into space, almost closer to sound design at times. A little like the kind of sound that accompanies a contemporary science fiction film. It’s a massive, luminous sound mass, ephemeral and dreamy. It's a place to lose yourself in. I think today, more than ever, Kayn fits into our music world. In fact, he probably sits much more comfortably today than he ever has in a sense. His name might not be as familiar as many of his peers, his approach and body of work has laid the ground for many other creatives. Listening to his work demonstrates that the path less taken can offer deep and profound influence, be it on musicians, visual artists, or even just a way of life. In some ways, Kayn offered us the future long before we even knew what it was.