Women During the Second Republic

MODERN WOMEN

In the aftermath of the First World War talk was swelling of “the modern woman” and, despite describing a very limited group of women, became a striking social phenomenon during the 1920s and 1930s. Las modernas, modern women who largely came from liberal bourgeois or upper class families, managed to break down the barriers imposed upon women, branching off, with some difficulty, from the path laid out before them — engagement, marriage, children, homemaking — in search of new horizons from which to reach fulfilment as independent beings. Thus, and even against fierce family and social opposition, they gradually managed to gain access to education and culture, both of which were pivotal to women’s desire to take up a professional vocation. This allowed many of them to construct a liberal political awareness, influenced by the contribution of political associationism, and they considered themselves to be feminists or had kept track and were aware of debates around the emancipation of women. Just as they had made incursions into schools and universities, they would do the same in theatres and cinemas, dances and cafés, discussion groups and clubs, becoming part of traditionally male culture.

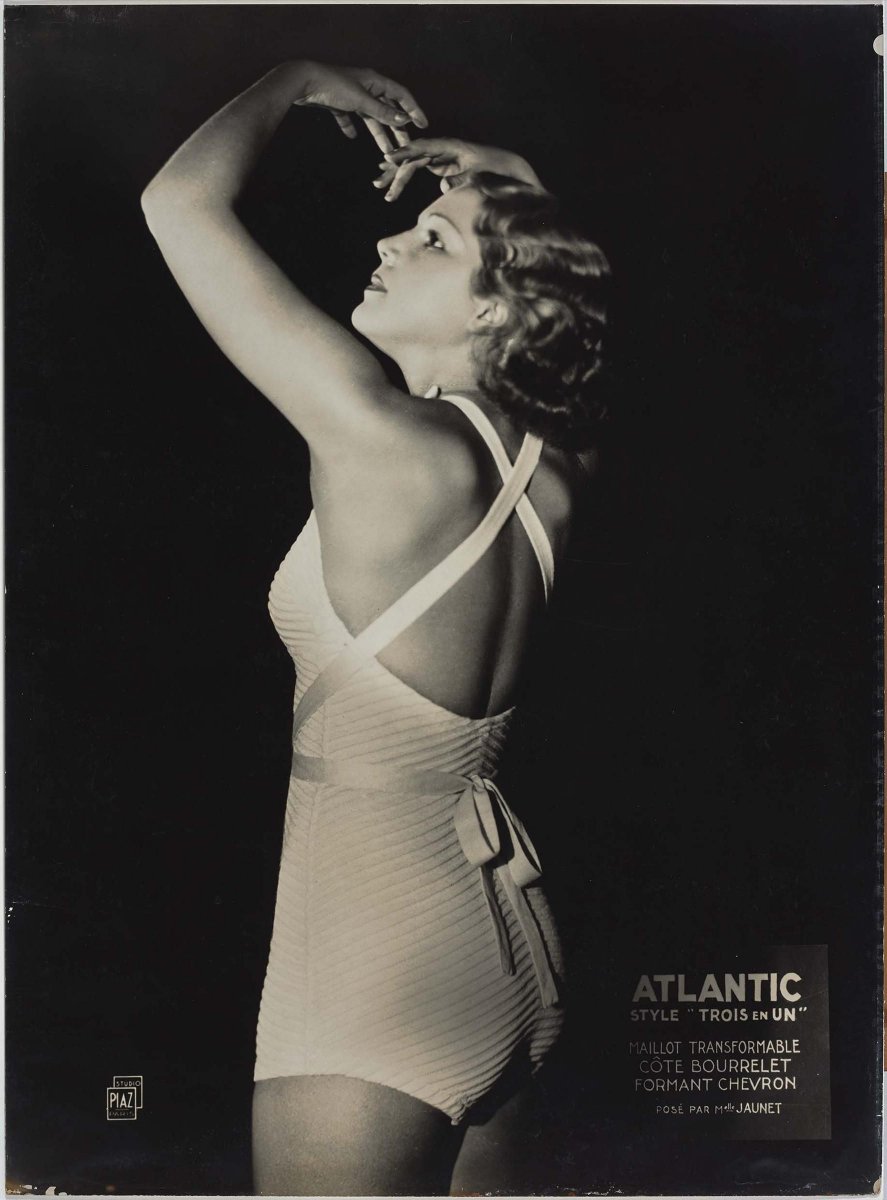

Anonymous photograph. Atlantic Style. Three in One, ca. 1935

See in the Collection

Modernity would be reflected in women’s physical appearance and the way they dressed, hence the importance of fashion in echoing new activities and facets of this modern woman, freeing her from the restraints and restrictions of the past, both literally and metaphorically. Above all, this fashion would arrive from the USA through cinema and advertising, with women acquiring the habit of smoking, wearing make-up and gaining a suntan, frowned-upon customs at the time. These changes to women’s image were disseminated primarily in graphic illustrations and magazines, displaying an enhanced image of the dynamic, energetic and independent woman who played sports, travelled alone, wore loose-fitting cloths and trousers, had short hair and gradually joined the world of work.

Women, from the Crónica: Weekly Magazine, special spring issue, 1934. Madrid: Prensa Gráfica, (1929–1939). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

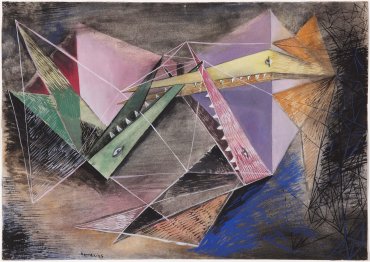

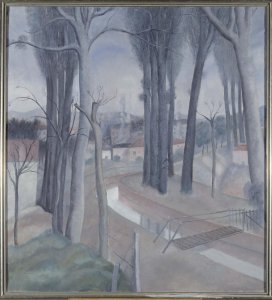

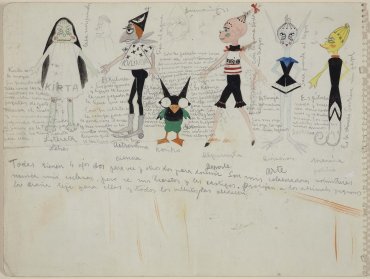

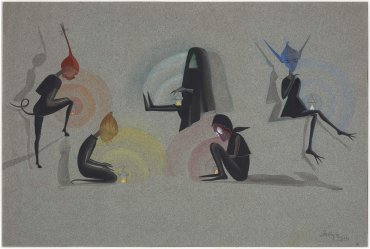

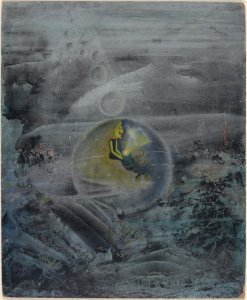

During the years of the Second Republic, the major modernising and Europeanising organisations, such as the Pedagogical Missions and the heirs of the Free Institution of Education, would implement the institutionalisation of popular culture, particularly with respect to dance and theatre, spheres where the presence of women was growing in importance. Women artists, professionally lowered in rank from the practice of the “great painting” reserved for men through greater widespread regard, engaged in avant-garde languages by way of other genres where they were accepted, for instance stage designs, theatre illustrations and dance choreographies, thereby contributing to broadening the horizons of Spain’s visual arts.

Education

In the final third of the 19th century, significant changes took place for women in Spain’s education system. One of the first projects related to these changes was the Association for the Education of Women (AEM), created in 1870 by pedagogue Fernando de Castro to push for women’s access into academic education, fostering their incorporation into the professional world and promoting social equality.

Ángeles Santos, Tertulia (The Gathering), 1929

See in the Collection

The Association was linked to the Free Institution of Education (ILE, 1876) since the time of its founding, and with its model based on pedagogical restoration through Krausism an idealist doctrine that advocated academic freedom from dogmatism —becoming an option of liberal, public, secular and free education as opposed to Church-directed educational tradition. Among its initiatives were the Extended Studies Board (JAE, 1907), the creation of the School Institution (1918), the Pedagogical Missions (1931) and the Santander International Summer University (1932). Propelled by the arrival of the Republic in 1931, for which education was a cornerstone of democracy’s social commitment, these institutions fostered women’s access across all levels of education.

The Extended Studies Board promoted the creation of the Residence for Young Ladies (1915–1936), which would become a salient cultural focal point in parallel with the better-known men’s version, the Residence for Students. At the time of its creation, it gained the support of the International Institute for Girls in Spain, founded by Alice Gordon Gulick in 1892 and established in Madrid in 1903 in the International Institute in Calle Miguel Ángel.

The aim of the Residence for Young Ladies, directed by María de Maeztu, was to champion women’s higher education, with the residents, a small group of women from liberal families, arriving in Madrid from the provinces to enrol in university faculties and departments, the Higher School of Teaching and the National Music Conservatoire, and so on. Initially, most enrolled in studies considered for women, such as Teaching or Nursing, although gradually interest in professional careers like Chemistry, Pharmacology and Law began to take root. For women to complete their education, or for those opting for unofficial training, the Residence was equipped with a laboratory and library, and a programme of master classes, lectures, concerts and readings that added impetus to the comprehensive preparation of a model professional and independent woman that was at the forefront in that era. Ready to undertake a qualified profession, these women contributed to the start of the transformation of a traditional social model associated with the female condition.

In the Residence, other initiatives also surfaced, such as the Female University Youth (1920) and the Lyceum Women’s Club (1926), both presided over by María de Maeztu. The former fast became part of the International Federation of University Women (FIMU), with a head office in London, while the Lyceum was created in accordance with international club models. The halls of the latter provided the setting for major controversies, where this active minority would spark debates on unjust laws for women, emancipation, civil rights, and women’s suffrage. It also became a major reference point in women’s artistic activity in Madrid at the time — women artists such as Marisa Roësset, Juana Francisca Rubio, Ángeles Santos and María and Helena Sorolla displayed their work there.

Josefina Carabias, “The thousand female students from the University of Madrid”, in Estampa: The Graphic Art and Literary Magazine on Current Affairs in Spain and Worldwide, No. 285, 24 June 1933. Madrid: Suc. de Rivadeneyra, 1928-(1938?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

Women Intellectuals and Artists

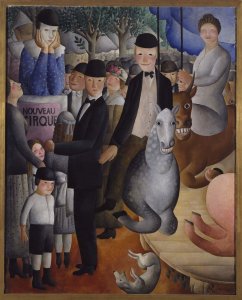

Maruja Mallo, La verbena (The Fair), 1927

See in the Collection

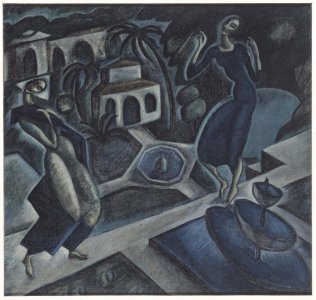

Part of the Generation of ’27, and with different ties to the Residence for Young Ladies, women intellectuals and artists from this era have been lost in an androcentric historiography of literature, thought and the arts. These women aimed to set forth a new vision of the world from their own perspective, moving away from the aesthetics and content of the 19th century. Their bid for modernity entailed reclaiming an overtly emancipated personal voice as they referred to predecessors who had started the debate around the emancipation of women and their role in society, for instance Teresa Claramunt, Carmen de Burgos and Emilia Pardo Bazán. Essentially, they were modern women ahead of their time, influenced by the regenerating and progressive environment that flowed from the ILE.

The work of women writers and thinkers was undervalued or ignored in comparison to their male contemporaries, who were often friends or partners. Rosa Chacel, Ernestina de Champourcin, Carmen Conde, Josefina de la Torre, María Teresa León, Concha Méndez and María Zambrano were exponents of modernity and the avant-garde, despite not holding a legitimate place that was befitting in the context of their generation.

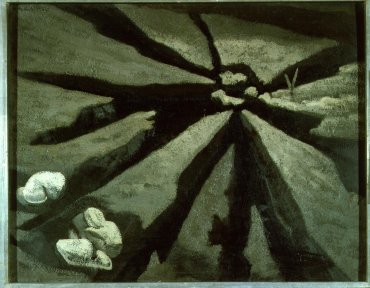

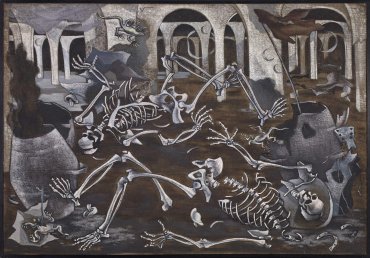

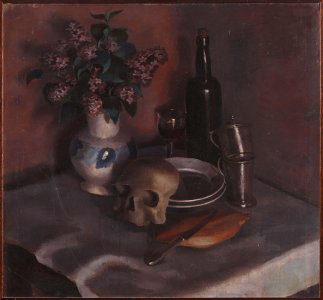

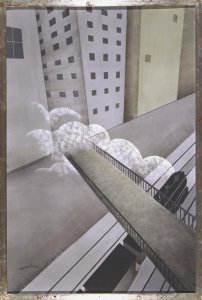

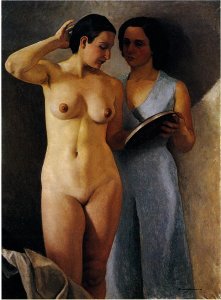

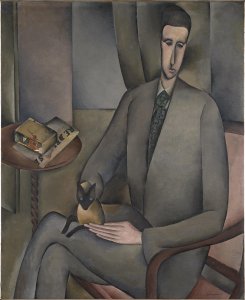

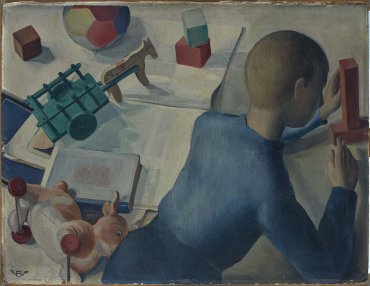

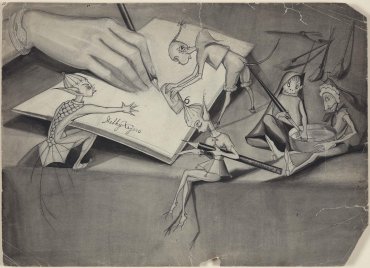

Similar to women intellectuals, women’s presence in art and life had been extremely limited as they endured stereotyped criticism on the female condition and were talked about as “young ladies” that painted. The dawn of the 20th century ushered in the consolidation of professional women artists — some had attended the San Fernando Advanced School of Fine Arts — also considered enterprising, modern and free women. Francis Bartolozzi ("Pitti"), Rosario de Velasco, Maruja Mallo, Julia Minguillón, Ángeles Santos and Delhy Tejero all searched for a new iconography, adopting avant-garde languages and concerns in their work around -isms, synonymous with the modernity of that era.

Yet for many women, the most widely accepted art genres were still those considered inferior, such as decorative arts and illustration work, but which contributed to building and disseminating the image of the modern woman by incorporating themes around playing sports, leisure, etc. Rosario de Velasco, Marga Gil Roësset, Maruja Mallo, Pitti and Delhy Tejero were thus joined by other names like Victorina Durán, Viera Sparza, Ángeles Torner Cervera, among others. Some 105 female illustrators would contribute to the Blanco y Negro magazine and ABC, culminating most notably with the Salon of Draughtswomen held at the Lyceum Women’s Club in March 1931. The exhibition constituted a landmark in displaying women’s art work in Spain during this period, underscoring how these women artists looked for an alternative professional opening to the practice of painting and the obstacles it posed for them.

The championing of modernity and rebellion against a conservative social and art system would witness one of its most transgressive points the day Salvador Dalí, Federico García Lorca, Maruja Mallo and Margarita Manso took off their hats in the centre of Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, scandalising passing pedestrians owing to the obligation for women from the upper and middle class to wear a hat. Maruja Mallo recalled: “People thought we were completely immoral, as though we weren’t wearing any clothes, and it took them no time to attack us in the street”. The action, drawing inspiration from the premise of liberating ideas oppressed under a hat, set a precedent for that group of intellectuals who tried to disassociate themselves from the bourgeoisie, breaking conventionalisms personally and professionally. Today, under the name of Las Sinsombrero (Hatless Women), this whole generation of women artists and intellectuals who fought for visibility in their own time are brought together as a group.

Noreste magazine, No. 10, spring 1935. Zaragoza: Noreste, 1932–(1936). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

Works in the Collection