Cargando...

Ángeles Torner Cervera (a.t.c.), cover of Y: The National Female Unionist Magazine, No. 18, July 1939. Madrid: Women’s Section of Falange Española and the Women Traditionalists of the JONS (Councils of the Nationalist Syndicalist Offensive, 1938–(1945?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

“Comrades, we now have our magazine, the magazine for nationalist-unionist women. It contains everything we need: our codes of conduct, based on the spirit of the new Spain, guidance for us to adhere to, examples to follow, and, mixed with spiritual inspiration, our magazine also features a children’s corner, pages of chores, fashion and cooking. In short, everything we women need”.

These words defined Y magazine, the first journal for women from the Women’s Section and directed by Marichu de la Mora and published from 1938 to 1946. Y was the vehicle through which the new fascist regime set out its model of women and society, extolling the role of mother and wife that was attuned to the interests of the regime. The magazine was printed in San Sebastián due to its proximity to the French border and the ease of access to high-quality raw materials for its publication. The signed texts were predominantly written by men, although a number of women did appear as illustrators, for instance María Claret, María de los Ángeles López Roberts y Muguiro, also known as Neneta, Marisa Roësset, a.t.c., Ángeles Torner Cervera’s pseudonym, and Rosario de Velasco, to mention but a few.

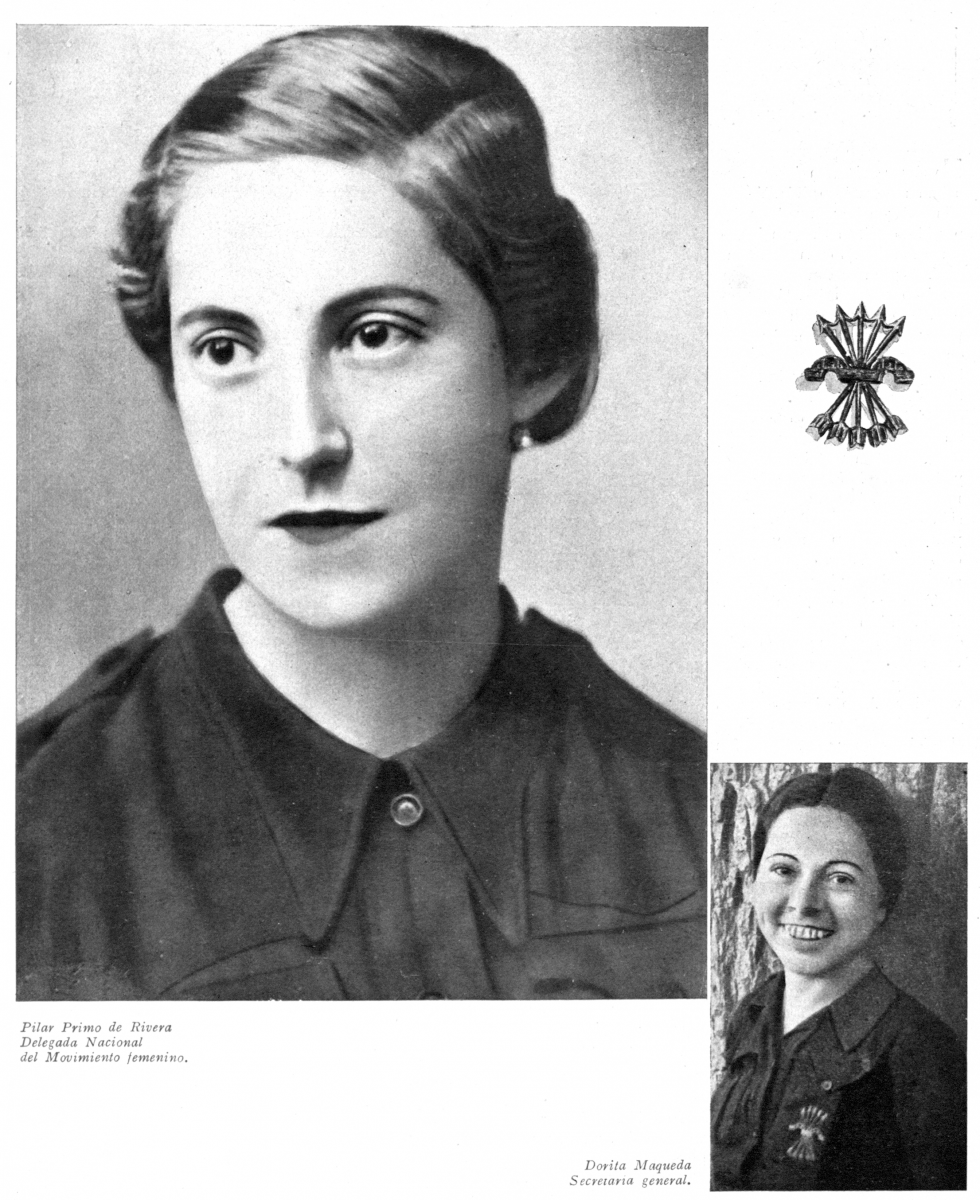

Portrait of Pilar Primo de Rivera, Y: The National Female Unionist Magazine, No. 1, February 1938. Madrid: Women’s Section of Falange Española and the Women Traditionalists of the JONS (Councils of the Nationalist Syndicalist Offensive), 1938–(1945?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

Y was identified with the Falange’s patriarchal ideology, whereby women took on a subordinate role to men, a role characterised by terms such as submission, service and selflessness, all of which ran through the breadth of the magazine. It was defined by José Antonio Primo de Rivera in the following terms: “We are not feminists either. We do not understand how respecting women entails taking them out of their magnificent destination and placing them in male responsibilities. I’ve always been saddened to see women in men’s practices, going to great lengths and deranged in a rivalry which leads — between the unwholesome indulgence of male competitors — to a defeat for all women. True feminism should not involve women wanting roles which today are deemed superior, but should instead surround women’s roles with increasingly greater human and social dignity”.

“Pilar Primo de Rivera in Germany”, Y: The National Female Unionist Magazine, No. 4, May 1938. Madrid: Women’s Section of Falange Española and the Women Traditionalists of the JONS (Councils of the Nationalist Syndicalist Offensive), 1938–(1945?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

Until the end of the Second World War, Y sympathised with the fascist ideology of the Axis powers with articles on Hitler and Mussolini, for instance the article on the above-mentioned Pilar Primo de Rivera’s trip to visit Hitler or those centred on the NS-Frauenschaft, Germany’s National Socialist Women’s League.

![“El Fuero del Trabajo y la mujer”, Y: revista de la mujer nacional sindicalista, n.º 4, abril de 1938. [Madrid]: Sección Femenina de Falange Española y Tradicionalistas de las JONS, 1938-[1945?]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS “El Fuero del Trabajo y la mujer”, Y: revista de la mujer nacional sindicalista, n.º 4, abril de 1938. [Madrid]: Sección Femenina de Falange Española y Tradicionalistas de las JONS, 1938-[1945?]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/coleccion/mujeres-guerra-civil/bloque-V/maria_de_la_hoz_0.png)

“The Labour Charter and Women”, Y: The National Female Unionist Magazine, No. 4, April 1938. Madrid: Women’s Section of Falange Española and the Women Traditionalists of the JONS (Councils of the Nationalist Syndicalist Offensive), 1938–(1945?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

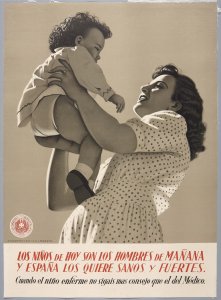

Y magazine, attuned to Francoism’s Labour Charter of 1938, saw family as the bedrock of society and relegated the married women to a role of domesticity. It actively took up a position against women’s work outside the home, coming to consider it as harmful and referring to it as a social plague with severe effects on health, motherhood and birth rates, with the last of these one of the regime’s priorities, as indicated by Doctor Luque in the first issue of the magazine: “In the State, mothers must be the most important citizen. These were the words published by Hitler in his Official Programme, and, as we know the reasons behind it and know the importance for our country at the present time of attaining a large number of healthy children from strong mothers, we do not simply want words but also actions so we can work together to achieve this end”.

![“Auxilio Social”, Y: revista de la mujer nacional sindicalista, n.º 1, febrero de 1938. [Madrid]: Sección Femenina de Falange Española y Tradicionalistas de las JONS, 1938-[1945?]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS “Auxilio Social”, Y: revista de la mujer nacional sindicalista, n.º 1, febrero de 1938. [Madrid]: Sección Femenina de Falange Española y Tradicionalistas de las JONS, 1938-[1945?]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/coleccion/mujeres-guerra-civil/bloque-V/auxilio_social.png)

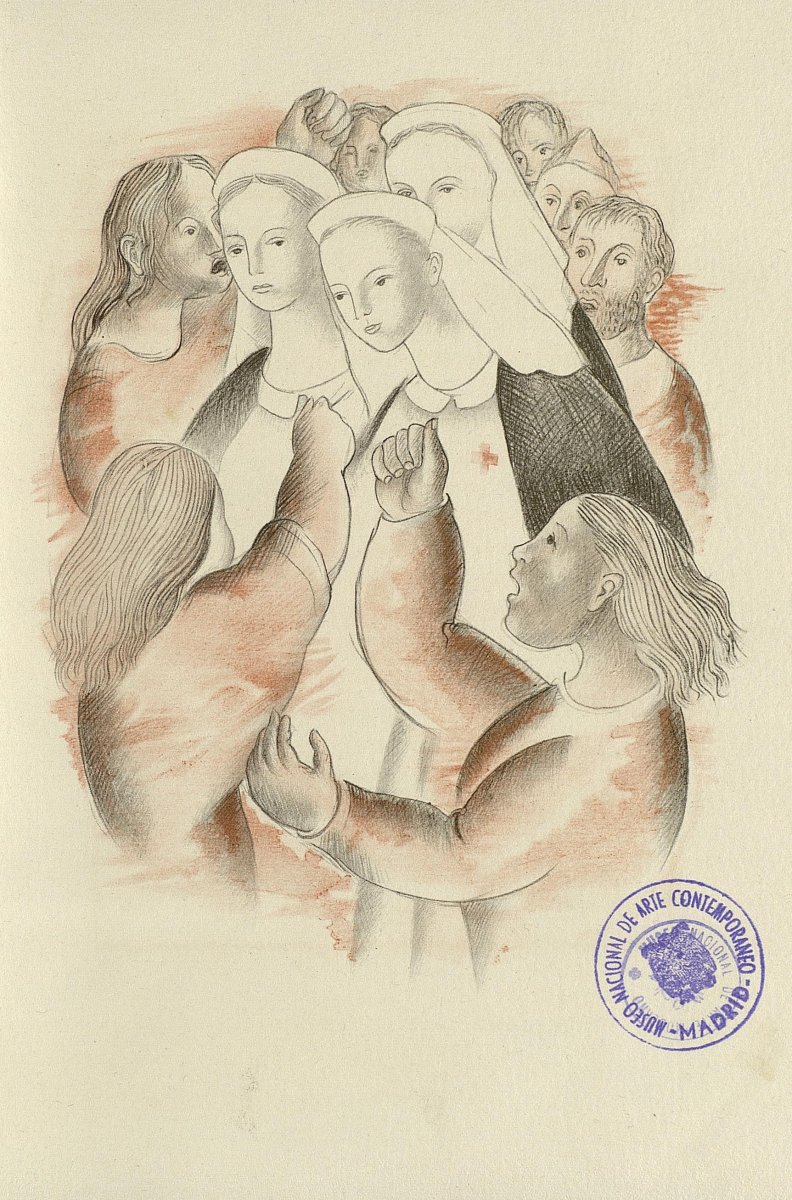

“Social Aid”, Y: The National Female Unionist Magazine, No. 1, February 1938. Madrid: Women’s Section of Falange Española and the Women Traditionalists of the JONS (Councils of the Nationalist Syndicalist Offensive), 1938–(1945?). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

One professional activity tolerated for women during the early years of Francoism was social work, via infirmaries and laundry facilities on the front, and hospitals and Auxilio Social (Social Aid) centres in the rearguard. Auxilio Social — initially Auxilio de Invierno (Winter Aid) — was the main public aid organisation for the most destitute, particularly the women and children of Republicans. Founded in October 1936 by Mercedes Sanz-Bachiller, it would quickly be absorbed by the Women’s Section in 1937. Moreover, its social objectives turned into a powerful propaganda campaign in both the Nationalist and Republican factions, as demonstrated in Salinas’s poster Franco’s Spain Has Broken Through! designed to be pasted on the walls of cities recently taken by Franco’s forces.

Fashion items in Y, extraneous to the situation of war engulfing Spain, reflected the latest trends in French fashion. Chanel, Lanvin and Maggy Rouff models shared a stage with the blue shirts of the Falange, first communion dresses and aprons “which will allow you to dedicate your time to domestic tasks but without foregoing the playfulness and grace that should be with you at all times”. This unfolded with illustrations in an elegant and frivolous style — characteristic of pre-war luxury lifestyle magazines — by artists such as Teodoro Delgado, Roberto Martínez Baldrich and Ángeles Torner Cervera (a.t.c).

Concha Espina, Princesses of Martyrdom. Barcelona: Ediciones Armiño / Gustavo Gili, (1940), (illustrations by Rosario de Velasco). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

One of the biggest artistic events from this period was the International Exhibition of Sacred Art, held in Vitoria in the summer of 1939 and overseen by Eugeni d’Ors, the incumbent head of the National Service of Fine Arts. The exhibition sought to bring a modern style into religious art so as to provide guidelines for reconstructing the vast number of churches destroyed during the Civil War. The exhibition featured a strong representation of women artists: Rosario de Velasco, Julia Minguillón and Marisa Roësset, and lesser-known artists such as María de Cardona, Mercedes Llimona and Margarita Sans Jordi.

![Rosario de Velasco, Sello de homenaje al ejército, 1939 [Grabado, Sánchez Toda] Rosario de Velasco, Sello de homenaje al ejército, 1939 [Grabado, Sánchez Toda]](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/coleccion/mujeres-guerra-civil/bloque-V/sello.jpg)

Rosario de Velasco, Homage to the Army Stamp, 1939, (etching by Sánchez Toda). Courtesy of the Rosario de Velasco Heirs

At that juncture, many of the foremost women artists from the 1930s had been forced into exile on account of their allegiance to the Republic. Manuela Ballester, Victorina Durán, Maruja Mallo and Remedios Varo were among the artists compelled to continue their careers overseas and they would not return to Spain for decades. Unlike many other female artists, Francis Bartolozzi (“Pitti”) and Delhy Tejero had to submit to the country’s new political situation and adapt their work to a new artistic reality, centring their practice on regional or religious themes. In their oeuvres, both combined illustration with mural painting, in particular Delhy Tejero, who would also make incursions into abstract painting during the 1950s and participate in the Santander International Exhibition of Abstract Art in 1953 and in a number of Hispano-American biennials. Women artists more closely affiliated with the new regime, such as Teresa Condeminas, Rosario de Velasco and Marisa Roësset, carried on with their careers without much ado, staying true to figurative painting proliferated by portraits, religious painting and genre painting, and in line with the official tastes that prevailed at different national events and exhibitions held in the 1940s. Julia Minguillón would become one of the biggest names from that time, ultimately earning first prize in the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1941 with the work Escuela de Doloriñas (Doloriñas School). She also participated in an array of exhibitions, most notably the 1942 Venice Biennale and the Círculo de Bellas Artes Biennial in 1947 in Madrid.