Stereotypes of Women

Spain in the 1960s and 1970s

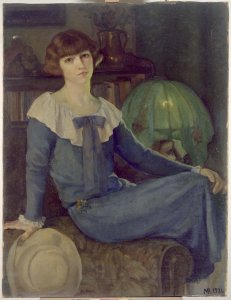

Images from the Second Republic

A Shifting Paradigm

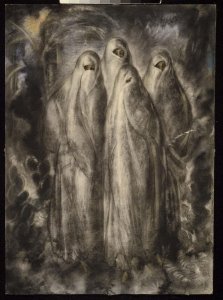

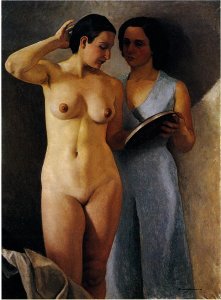

Francoism established a new legal order that upheld male supremacy in a counter-revolution of gender, a tabula rasa from the rights and liberties obtained in the Second Republic. This “return to order” was a key component in the repressive machine, disciplinary power and the patriarchal, nationalist-Catholic society of the dictatorial regime. By dint of laws, regulations, education models and the Sección Femenina — the Women’s section — Francoism drove a demure and obedient female stereotype, banishing women from the public sphere and returning them to their only authorised spaces: home and family.

Women’s Education and Francoism

Learning aligned to building “good” Catholic wives and mothers began with the reading of fairy tales, toys, education in the home and formal education, imagery launched by the media in serials, agony aunts and in cinema, and continued through society-imposed restrictions.

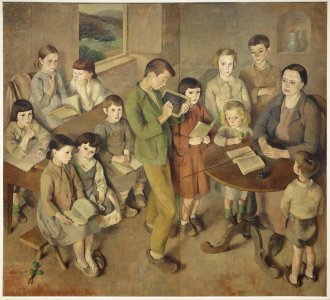

During the Franco regime, girls from the upper classes went to religious schools, and some went on to higher education. Those who entered a profession left it behind once they married in order to tend to their husband and children. Something similar occurred in the middle classes, who dedicated their time to housework:

Azucena Notebooks of Housework and Stories, 1950. Library and Documentation Centre. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid

All girls were taught religion, housework, cooking and home-making; teenage girls dressmaking, and those who attended courses in the Women’s Section the basics of childcare and caring for the sick. Girls from poorer families were only enrolled at school for a few years and without finishing elementary education, working in service, factories or workshops. Female workers from the primary sector were never accounted for in surveys, nor were their partners. Those from the poorest backgrounds often ended up in prostitution.

Women’s Section and a Women’s Magazine:

Emancipatory Education Formulas

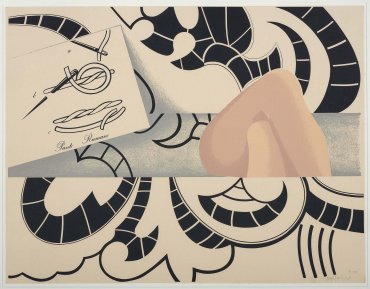

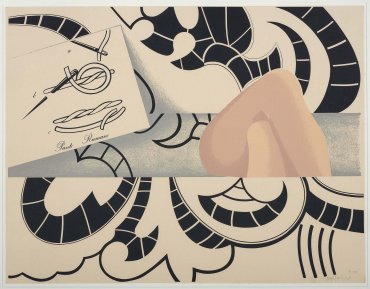

Faced with such restrictive training, some women artists decided to intertwine their work in education formulas that used art as emancipation. A process of re-assessing art techniques traditionally identified with women and which had been an important part of their childhood education, for instance needlework and fabrics, began.

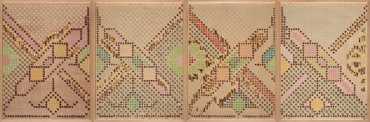

In Bordados (Embroidery, 1974) Ángela García Codoñer criticised beauty contests and crossed them with a tirade against another of Francoism’s tools to control and “educate” Spanish women from childhood: learning housework (presumably this would be of use as adults for women to adequately fulfil their role as mothers, wives, housewives). In De profesión: sus labores (Occupation: Housewife, 1972–1974), Isabel Oliver also evinced how dressmaking and embroidery hid a kind of ordinariness.

Mari Chordà linked her artistic production to an ethics of care, making works that advocated lucid and free learning in childhood, such as Joguet per l’Àngela (Toy for Angela, 1969). It is worth noting that primary education chiefly fell under the responsibility of schoolmistresses and considered women more suited to adaptive artistic specialities (designing objects) and reproductive (teaching) than those conceived as purely creative, and were thus attuned with individual freedom personified in the “male disposition”.