Emancipation Under Guardianship

Women’s Legal Status

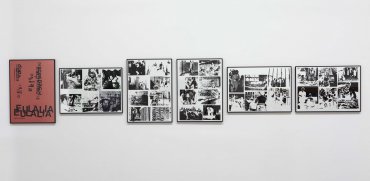

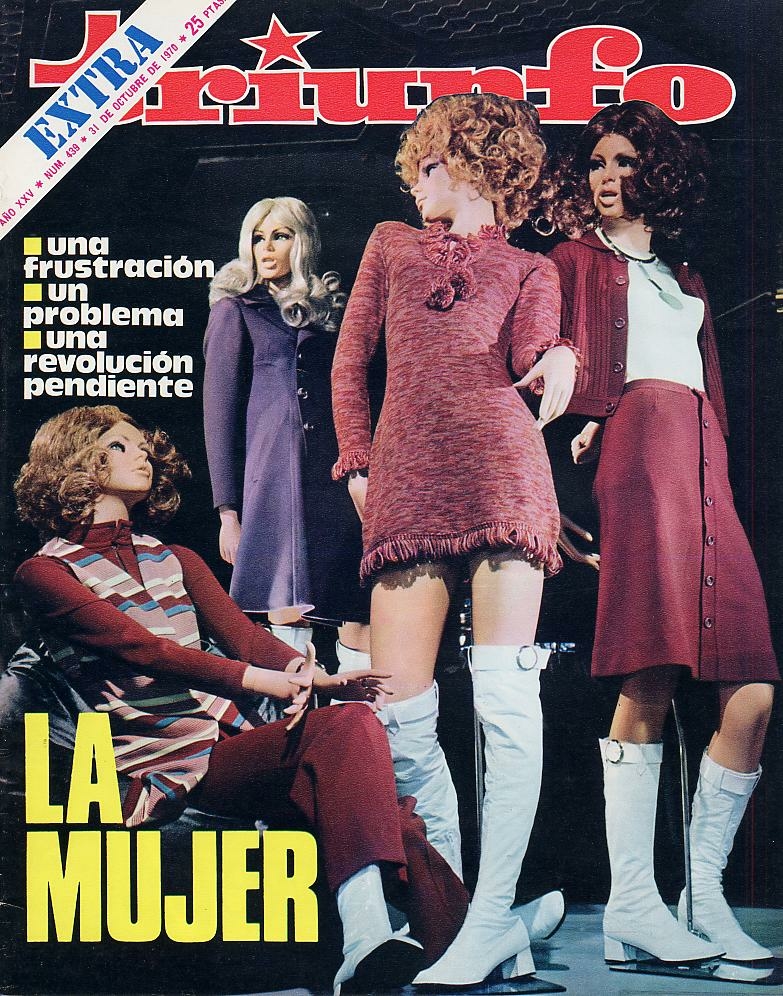

Triunfo, cover, No. 400, year XXV, 21 October 1970. © Courtesy of Triunfo Digital

During Late Francoism, abortion, divorce and the free use of contraception were all prohibited. The situation of inequality for women in a sexist dictatorship engendered social and political protests that differed from their European and American peers.

They were minors in terms of private law — unable to acquire assets or travel without the permission of the man on which they depended, be it father or husband — and also lacked guardianship over their children. Nevertheless, they were of legal age in issues related to criminal law; for instance, adultery was a law exclusively applicable to women.

For women, gaining full-time employment was also far from easy, although Spain’s industrialisation upon moving out of autocracy brought with it an increased demand for labour, regulated by the Equality Law for Women’s Political, Professional and Labour Rights (1961). This law would allow women to access many professional careers (with the permission of fathers, tutors and husbands), but banned them from the judicature and army; it also suspended forced leave of absence previously stipulated for women upon marriage.

The resurgence of feminism was a response to the dictatorship, brought about by a lack of political liberties and discrimination towards women, and was paramount in democratising society, with feminist branches existing covertly in the main political parties — particularly salient was MDM (Women’s Democratic Movement) at the heart of the Spanish Communist Party.

Demonstrations of Resistance

Women artists operating in the Spanish art scene were considered rare exceptions, and belittling their talent by using the epithet “female” was commonplace in critique and in the media, thereby taking them out of contingency to link their output to immutable essences.

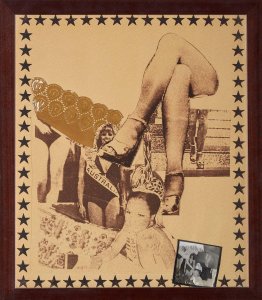

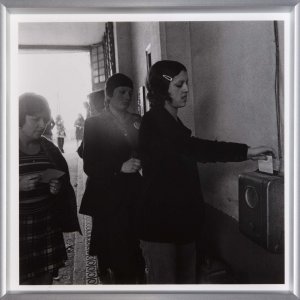

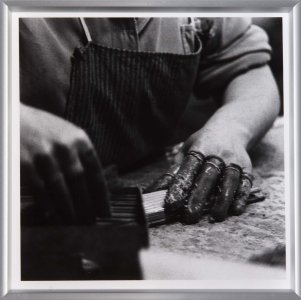

With traditional artistic languages and aesthetic and moral values tainted by the patriarchy’s excluding practices, many of these women Pop artists became part of articulating new forms of art-making and consuming art, making hybrid works with conceptual influences and drawing from photography, performance, installation, embroidery, film and video. Many of the pieces from the series Etnografía (Ethnography) by Eulàlia Grau relinquished painting to make use exclusively of transfer, while the work of García Codoñer retrieved collage techniques and crossed them with electrography to create amalgamations with press cuttings, photocopies, lacework and painting.

The pieces of these artists are, therefore, political and coincide with the feminist discourses of the time — analysing the situation of labour inequality, denouncing the continued prevalence of stereotypes, demanding sexual freedom. Moreover, they were discourses encapsulated under the broad umbrella of “social issues”, as reflected in the publications from that era: